Poetry Dispatch No. 254 | October 4, 2008

POET/OBIT

(Another chapter of “THE WRITING LIFE”)

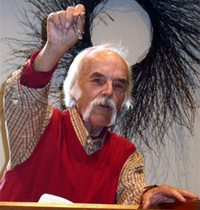

HAYDEN CARRUTH 1921 – 2008

Silence

by Hayden Carruth

Sometimes we don’t say anything. Sometimes

we sit on the deck and stare at the masses of

goldenrod where the garden used to be

and watch the color change form day to day,

the high yellow turning to mustard and at last

to tarnish. Starlings flitter in the branches

of the dead hornbeam by the fence. And are these

therefore the procedures of defeat? Why am I

saying all this to you anyway since you already

know it? But of course we always tell

each other what we already know. What else?

It’s the way love is in a late stage of the world.

from “Collected Shorter Poems” Copper Canyon Press, 1992

![]()

Hayden Carruth, 87; Poems Reflected Struggles of Life

By Matt Schudel

Washington Post Staff Writer

Wednesday, October 1, 2008; B05

Hayden Carruth, whose forceful observations of nature, hard work and mental illness brought him late acclaim as one of the most important poets of his generation, died Sept. 29 at his home in Munnsville, N.Y., after a series of strokes. He was 87.

Hayden Carruth, whose forceful observations of nature, hard work and mental illness brought him late acclaim as one of the most important poets of his generation, died Sept. 29 at his home in Munnsville, N.Y., after a series of strokes. He was 87.

Mr. Carruth (pronounced kuh-RUTH) lived for many years in rural Vermont and New York, where manual labor and an unforgiving climate became part of his daily life and, ultimately, his poetic voice.

Through years of isolation and neglect, he doggedly continued to write, gaining belated recognition for his more than 30 books. A 1996 Virginia Quarterly Review article described him as “certainly one of the most important poets working in this country today.”

His “Collected Shorter Poems, 1946-1991” received the 1992 National Book Critics Circle award for poetry, and he won the National Book Award for the collection “Scrambled Eggs & Whiskey” in 1996. After decades of living hand to mouth, he won two prestigious awards, the $25,000 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize in 1990 and the $50,000 Lannan Foundation literary award in 1995.

Mr. Carruth began writing at 6 and became a master of poetic diction, from the grandly formal to the bluntly vernacular. He wrote in a deceptively simple style that often evoked nature as he explored philosophical themes of sorrow, loneliness and human dignity.

“His poems take on a variety of voices: the farmers he lived among in Vermont, the jazzmen whose music he reveres, the ancient Chinese poets who taught him,” author Lynne Sharon Schwartz wrote in the Chicago Tribune in 2005. “He has written in the voice of lover, war protester, mental patient, grieving son and father.”

In 1953 and ’54, Mr. Carruth was treated in a New York mental hospital for 18 months for alcoholism and a nervous breakdown. He received electroshock therapy and emerged, he said, “in worse shape” than when he went in. But his prolonged stay gave him a chance to study existential philosophy, which influenced his later writing.

Seldom overtly political in his writing, Mr. Carruth nonetheless had strong views, which he expressed in an angry letter to the New York Times in 1971, after the newspaper’s editorial about the Attica prison riot appeared on the same page as “my stupid poem about the flowers of summer.”

“I think it will be a long time before our civilization will have much use for flowers or poems again,” he concluded.

Hayden Carruth was born Aug. 3, 1921, in Waterbury, Conn. His father and grandfather were journalists, and he learned to write at his grandfather’s knee. He graduated from the University of North Carolina in 1943 and served in the Army Air Forces in Italy during World War II.

Mr. Carruth received a master’s degree in English from the University of Chicago in 1948. He was the editor of Poetry magazine in Chicago and worked for the University of Chicago Press before his nervous collapse.

Seeking solitude after his hospitalization, Mr. Carruth moved to northern Vermont and worked as a farm laborer, mechanic, freelance writer and editor.

“I had to live a very secluded life, but I’m not sorry that’s the way it turned out,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1990. “The main disadvantage was poverty.”

In 1966, he had received a $10,000 federal grant, but three years later his gross income was only $600. At times, he had to steal corn intended for cattle. But he was drawn to “the honest country people, the laborers, and people who had real folk habits in their speech. I loved to listen to them, and tried to imitate them in my poems.”

He was also strongly influenced by his love of jazz and tried to imitate its improvisational qualities in his poetry.

Mr. Carruth published his first book of poetry in 1959, but his major critical breakthrough didn’t come until the 1970s. His only novel, a tale of adultery called “Appendix A,” appeared in 1963 to dismissive reviews.

After teaching in Vermont for a few years, Mr. Carruth joined the faculty at Syracuse University in Upstate New York in 1979. He was poetry editor of Harper’s magazine from 1977 to 1982.

Despite his newfound professional security, he suffered another mental setback in 1988 and nearly died after swallowing every pill in his home. He recovered and wrote that his suicide attempt helped “unify my sense of self, the sense which had formerly been so refracted and broken up.”

Despite his newfound professional security, he suffered another mental setback in 1988 and nearly died after swallowing every pill in his home. He recovered and wrote that his suicide attempt helped “unify my sense of self, the sense which had formerly been so refracted and broken up.”

His marriages to Sara Anderson, Eleanor Ray and Rose Marie Dorn ended in divorce.

Survivors include his fourth wife, poet Joe-Anne McLaughlin of Munnsville; and a son from his third marriage.

A daughter from his first marriage, Martha, died in 1997, prompting him to write a heartfelt elegy published in his 2001 collection, “Doctor Jazz.”

One of Mr. Carruth’s final books, “Letters to Jane” (2004), was a volume of his correspondence with poet Jane Kenyon, who died of cancer in 1995 at 47.

“He wrote her a letter every week,” Kenyon’s husband, poet Donald Hall, said yesterday. “He did not talk to her about her disease. He wrote looking out his window at a bird, at a leaf falling. They were absolutely marvelous.”

![]()

Prepare

By Hayden Carruth

“Why don’t you write me a poem that will prepare me for your death? “you said.

It was a rare day here in our climate, bright and sunny. I didn’t feel like dying that

day,

I didn’t even want to think about it – my lovely knees and bold shoulders’ broken

open,

Crawling with maggots. Good Christ! I stood at the window and I saw a strange dog

Running in the field with its nose down, sniffing the snow, zigging and zagging,

And whose dog is that? I asked myself. As if I didn’t know. The limbs of the apple

trees

Were lined with snow, making a bright calligraphy against the world, messages to me

From an enigmatic source in an obscure language. Tell me, how shall I decipher

them?

And a jay slanted down to the feeder and looked at me behind my glass and

squawked.

Prepare, prepare. Fuck you, I said, come back tomorrow. And here he

is in this new gray and gloomy morning.

We’re back to our normal weather. Death in the air, the idea of death

settling around us like mist,

And I am thinking again in despair, in desperation, how will it happen?

Will you wake up

Some morning and find me lying stiff and cold beside you in our bed?

How atrocious!

Or will I fall asleep in the car, as I nearly did a couple of weeks ago,

and drive off the road

Into a tree? The possibilities are endless and not at all fascinating,

except that I can’t stop

Thinking about them, can’t stop envisioning that moment of hideous violence.

Hideous and indescribable as well, because it won’t happen until it’sover. But not for you.

For you it will go on and on, thirty years or more, since that’s the distance

between us

In our ages. The loss will be a great chasm with no bridge across it

(for we both know

Our life together, so unexpected, is entirely loving and rare). Living on your

own –

Where will you go? what will you do? And the continuing sense of

displacement

From what we’ve had in this little house, our refuge on our green or

snowbound

Hill. Life is not easy and you will be alive. Experience reduces itself to

platitudes always,

Including the one which says that I’ll be with you forever in your

memories and dreams.

I will. And also in hundreds of keepsakes, such as this scrap of a poem

you are reading now.

from SCRAMBLED EGGS & WHISKEY, Poems 1991-1995, Copper Canyon Press

much more on Hayden Carruth on his web site here…