NOTES from the UNDERGROUND No.168 | January 28, 2009

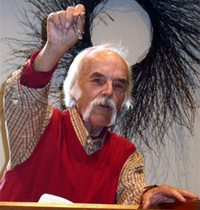

John Updike

March 18, 1932—January 27, 2009

On Memories, Beginnings, Endings…

To begin with the end: Updike dead at 76…another long, quiet, sleepless night…last night, yet so fully alive remembering, remembering, going through all the Updike books on my shelves, thinking as well–his death too close to home…a writer I began to follow from my own beginnings, his first stories, first books…learning so much, admiring/studying the craft…so conscious too of certain common denominators we shared in boyhood…a writer who could not separate himself from fiction, but rendered it all, everything into art. His sentences–not written but sculpted…divined. His stories held you hostage in the very first lines.

He was not Mailer or Hemingway or Bellow or Hunter. He confessed, often, his grasp was small, more mundane…quite ordinary. What else to work with, growing up rural, in Shillington, PA? (He smiled.)

And so it what childhood…memories held in safekeeping to last seventy-six years…mother, father, grandparents…the shadow of the great depression…the farm, the town, the city, the suburbs…friends, first love/many loves…marriage, wives, lovers, children, separation, divorce, remarriage, grandchildren, travel, fame…pages and pages, books and books. He owned up to it all. Made it real–no character, setting, feeling you were likely to ever forget. Be it the life and times of “Rabbit” Angstrom (surely an American masterpiece), or the tails and travails of Richard and Joan Maple. (And was there ever a greater story written on the breakup of a marriage than “Separating” loss, anxiety, etc.? Required reading for anyone who’s been there, is there, or seems headed toward that rite-of-passage. Then all those stories of childhood which seem written in gold, glowing there in afternoon sunlight, lingering forever in a way you’ll never be again.

If there is one book of stories (his earliest stories) I would suggest for a writer just starting out to learn the tale and tell it well…it would be a paperback collection (difficult to find) called OLINGER STORIES. The map is there. And needs to be studied carefully.

One other book I urge writers, in particular, keep on their shelves and read often: SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS, Memoirs by John Updike. A memory to take into your own consciousness and lead you where you need to go.

Here are a few excerpts from some of works mentioned above…in memory and love of an American writer who knows how story leads to story, without end. —Norbert Blei

![]()

The point, to me, is plain, and is the point, more or less, of all these Olinger stories. We are regarded unexpectedly. The muddled and inconsequent surface of things now and then parts to yield us a gift. In my boyhood I had the impression of being surrounded by an incoherent generosity, of—to quote a barefaced reminiscence I once wrote—a quiet but tireless goodness that things at rest, like a [ brick wall or a small stone, seem to affirm. A wordless reassurance these things are pressing to give. An hallucination? To transcribe middleness with all its grits, bumps, and anonymities, in its fullness of satisfaction and mystery: is it possible or, in view of the suffering that violently colors the periphery and that at all moments threatens to move into the center, worth doing? Possibly not; but the horse-chestnut trees, the telephone poles, the porches, the green hedges recede to a calm point that in my subjective geography is still the center of the world.

[from the “Foreward” to OLINGER STORIES, Vintage Books, 1964

Shortly before the first of these personal essays was composed (but several years after the soft spring night in Shillington that it describes) I was told, perhaps in jest, of someone wanting to write my biography—to take my life, my lode of ore and heap of memories, from me! The idea seemed so repulsive that I was stimulated to put down, always with some natural hesitation and distaste, these elements of an autobiography. They record what seems to me important about my own life, and try to treat this life, this massive datum which happens to be mine, as a specimen life, representative in its odd unique¬ness of all the oddly unique lives in this world. A mode of impersonal egoism was my aim: an attempt to touch honestly upon the central veins, with a scientific dispassion and curiosity. The veins had been tapped, of course—the lode mined—in over thirty years’ worth of prose and poetry; and where an especially striking or naked parallel in my other work occurred to me, I have quoted it, as a footnote. But merciful forgetfulness has no doubt hidden many other echoes from me, as well as eroded the raw material of autobiography into shapes scarcely less imaginary, though less final, than those of fiction.

[from the “Forward” to SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS, Memoirs by John Updike, Knopf, 1989.}

We are all of mixed blood, and produce mixed results. At a low time in my life, when I had taken an exit not from my profession but from my marriage, and left your mother and her siblings more in harm’s way than felt right, my mother in the midst of her disapproval and sadness produced a saying so comforting I pass it on to you. She sighed and said, “Well, Grampy used to say, ‘We carry our own hides to market.’ ” The saying is blunt but has the comfort of putting responsibility where it can be borne, on a frame made to fit. The comfort of my hearing it said lay of course in its partial release from tribal obligations—our debt of honor to our ancestors and our debt of shelter to our descendants. These debts are real, but realer still is a certain obligation to our own selves, the obligation to live. We are social creatures but, unlike ants and bees, not just that; there is something intrinsically and individually vital which must be defended against the claims even of virtue. Quench not the spirit. Do not hide your light beneath a bushel basket. Do not bury your talent in the ground of this world. In this grandfatherly letter about my paternal grandfather, whom I never knew, let me end by offering you, as part of your heritage, this saying ascribed to my other grandfather, John Hoyer, whom I knew well, who watched me grow from infancy and who lived in good health until he was over ninety. You carry your own hide to market.

Love, Grandpa

[“A Letter to My Grandsons”, from SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS, Memoirs by John Updike, Knopf, 1989.}

Not only are selves conditional but they die. Each day, we wake slightly altered, and the person we were yesterday is dead. So why, one could say, be afraid of death, when death comes all the time? It is even possible to dislike our old selves, these disposable ancestors of ours. For instance, my high-school self—skinny, scabby, giggly, gabby, frantic to be noticed, tormented enough to be a tormentor, relentlessly pushing his cartoons and posters and noisy jokes and pseudo-sophisticated poems upon the helpless-high school—strikes me now as considerably obnoxious, though I owe him a lot: without his frantic ambition and insecurity I would not now be sitting on (as my present home was named by others) Haven Hill. And my Ipswich self, a delayed second edition of that high-school self, in a town much like Shillington in its blend of sweet and tough, only more spacious and historic and blessedly free of family ghosts, and my own relative position in the “gang” improved, enhanced by a touch of wealth and celebrity, a mini-Mailer in our small salt-water pond, a stag of sorts in our herd of housewife-does, flirtatious, malicious, greedy for my quota of life’s pleasures, a distracted, mediocre father and worse husband—he seems another obnoxious show-off, rapacious and sneaky and, in the service of his own ego, remorseless. But, then, am I his superior in anything but caution and years, and how can I disown him without disowning also his useful works, on which I still receive royalties? And when I entertain in my mind these shaggy, red-faced, overexcited, abrasive fellows, I find myself tenderly taken with their diligence, their hopefulness, their ability in spite of all to map a broad strategy and stick with it. So perhaps one cannot, after all, not love them.

[“On Being a Self Forever”, from SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS, Memoirs by John Updike, Knopf, 1989.}

Even toward myself, as my own life’s careful manager and promoter, I feel a touch of disdain. Precociously conscious of the precious, inexplicable burden of selfhood, I have steered my unique little craft carefully, at the same time doubting that carefulness is the most sublime virtue. He that gains his life shall lose it. In this interim of gaining and losing, it clears the air to disbelieve in death and to believe that the world was created to be praised. But I inherited a skeptical temperament. My father believed in science (“Water is the great solvent”) and my mother in nature. She looked and still looks to the plants and the animals for orientation, and I have absorbed the belief that when in doubt we should behave, if not like monkeys, like “savages”—that our instincts and appetites are better guides, for a healthy life, than the advice of other human beings. People are fun, but not quite serious or trustworthy in the way that nature is. We feel safe, huddled within human institutions—churches, banks, madrigal groups—but these concoctions melt away at the basic moments. The self’s responsibility, then, is to achieve rapport if not rapture with the giant, cosmic other: to appreciate, let’s say, the walk back from the mailbox.

[“On Being a Self Forever”, from SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS, Memoirs by John Updike, Knopf, 1989.}

Many thanks for the excerpts and bio on John Updike – one of the true contemporary masters of the English language. He carved his slice of our world, and did it to perfection!

A wonderful tribute on your part, i enjoyed every bit of your Updike piece

Hey ! I am an old, very old (!) friend of Dale Norton’s. I grew up in Green Bay and only spent one summer in Ephraim but do love Door County so Dale gave me the link to your notes. Very cool job on Updike – He was so wonderful and I looked forward to every new writing that he did. An institution ! Thanks for the tribute.