PoetryDispatch No. 295 | September 27, 2009

CAROLYN FORCHÉ

When I do writing workshops occasionally, sometime during that first hour, first session, I toss out the question, especially to beginners:

“What kind of writer do you want to be?”

Always a good opener. Comfort zone. “We’re all in this together” kind of thing. A little laughter—the fairly predictable “rich and famous”—but gradually the room grows quiet. Some soul-searching going on. (This guy’s not smiling…he must be serious.)

They are waiting for me to explain. Give them an answer they can live with.

I think it’s always a valid question—for beginners. Others as well:

“What kind of a writer have you become?

It’s all I can do to try to answer that. All I can do to keep from swinging into a full-blown essay, chapter, ‘blog’… What’s happened? Are we writing what we’re really thinking, feeling, seeing? Any of us? Do we care? Is the subject here? Far away from here? Another country? Does it call us? Would we rather carry on with whatever it is we are writing which seems…self-fulfilling? Where, when, how, do we separate the personal from the social? Should it be separated? Whatever happened to “writers of conscience”? Has the system successfully/finally ‘corporatized’ conscience, turning it into a bad investment? Have the talk shows, the talking heads, the whole modern media bliz silenced writers from telling the true words in stories and poems? Is/was it all just ‘fiction’ after all? That whole Steinbeck, GRAPES OF WRATH thing? That black writer Richard Wright (NATIVE SON) bitching about life back there in Chicago, in his time? All those American and Latino writers (to this day) describing the terrors of life south of all the borders–how we are all a big part of the tyranny and repression. Has literary ‘concern’ over injustice in this country been reduced to the politics of rant rather than an act of art? (A bigger audience for ‘rant’; repression doesn’t sell.)

What kind of a writer do you want to be?

Look at Carolyn Forche’. Her book that covers ‘conscience’ world-wide … the anthology she edited in 1991: AGAINST FORGETTING Twentieth Century Poetry of Witness. This is the bible—a literary history of writers finding and voicing their own words against tyranny, injustice, the status-quo.

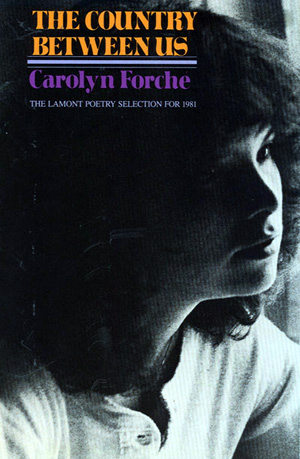

On the back cover of her own award winning book of poems, THE COUNTRY BETWEEN US, is a statement by another American poet of conscience, Denise Levertov, which brings this all full circle, a final perspective. —Norbert Blei

“Here’s a poet who’s doing what I want to do, what I want to see all of us poets doing in this time without any close parallels or precedents in history: she is creating poems in which there is no seam between personal and political, lyrical and engaged. And she’s doing it magnificently, with intelligence and musicality, with passion and precision.” –Denise Levertov

![]()

THE COLONEL

by

Carolyn Forché

WHAT YOU HAVE HEARD is true. I was in his house. His wife carried

a tray of coffee and sugar. His daughter filed her nails, his son went

out for the night. There were daily papers, pet dogs, a pistol on the

cushion beside him. The moon swung bare on its black cord over

the house. On the television was a cop show. It was in English.

Broken bottles were embedded in the walls around the house to

scoop the kneecaps from a man’s legs or cut his hands to lace. On

the windows there were gratings like those in liquor stores. We had

dinner, rack of lamb, good wine, a gold bell was on the table for

calling the maid. The maid brought green mangoes, salt, a type of

bread. I was asked how I enjoyed the country. There was a brief

commercial in Spanish. His wife took everything away. There was

some talk then of how difficult I had become to govern. The parrot

said hello on the terrace. The colonel told it to shut up, and pushed

himself from the table. My friend said to me with his eyes: say

nothing. The colonel returned with a sack used to bring groceries

home. He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like

dried peach halves. There is no other way to say this. He took one

of them in his hands, shook it in our faces, dropped it into a water

glass. It came alive there. I am tired of fooling around he said. As

for the rights of anyone, tell your people they can go fuck themselves.

He swept the ears to the floor with his arm and held the last

of his wine in the air. Something for your poetry, no? he said. Some

of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice. Some of the

ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.

May 1978

[from THE COUNTRY BETWEEN US, Harper & Row, 1981]

Carolyn Forché is an American poet, editor, translator, and human rights advocate. Forché was born in Detroit, Michigan, on April 28, 1950, to Michael Joseph and Louise Nada Blackford Sidlosky. Forché earned a B.A. in International Relations at Michigan State University in 1972. After graduate study at Bowling Green State University in 1975, she taught at a number of universities, including the University of Virginia, Skidmore College, Columbia University, and in the Master of Fine Arts program at George Mason University. She is now Director of the Lannan Center for Poetry and Poetics and holds the Lannan Chair in Poetry at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.. She lives in Maryland with her husband, Harry Mattison, a photographer, and their son, Sean-Christophe Mattison, who is a filmmaker.

Carolyn Forché is an American poet, editor, translator, and human rights advocate. Forché was born in Detroit, Michigan, on April 28, 1950, to Michael Joseph and Louise Nada Blackford Sidlosky. Forché earned a B.A. in International Relations at Michigan State University in 1972. After graduate study at Bowling Green State University in 1975, she taught at a number of universities, including the University of Virginia, Skidmore College, Columbia University, and in the Master of Fine Arts program at George Mason University. She is now Director of the Lannan Center for Poetry and Poetics and holds the Lannan Chair in Poetry at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.. She lives in Maryland with her husband, Harry Mattison, a photographer, and their son, Sean-Christophe Mattison, who is a filmmaker.

Forché’s first poetry collection, Gathering the Tribes (1976), won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Competition, leading to publication by Yale University Press. In 1977, she traveled to Spain to translate the work of Salvadoran-exiled poet Claribel Alegría. Upon her return, she received a Guggenheim Fellowship, which enabled her to travel to El Salvador, where she worked as a human rights advocate. Her second book, The Country Between Us (1981), was published with the help of Margaret Atwood. It received the Poetry Society of America’s Alice Fay di Castagnola Award, and was also the Lamont Poetry Selection of the Academy of American Poets. Her articles and reviews have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Nation, Esquire, Mother Jones, and others. Forché has held three fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, and in 1992 received a Lannan Foundation Literary Fellowship.

Her anthology, Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness, was published in 1993, and her third book of poetry, The Angel of History (1994), was chosen for The Los Angeles Times Book Award. Her works include the famed poem The Colonel. She is also a trustee for the Griffin Poetry Prize.

Though Forché is sometimes described as a political poet, she considers herself a poet who is politically engaged. After first acquiring both fame and notoriety for her second volume of poems, The Country Between Us, she pointed out that this reputation rested on a limited number of poems describing what she personally had experienced in El Salvador during the Salvadoran Civil War. Her aesthetic is more one of rendered experience and at times of mysticism rather than one of ideology or agitprop. Forché is particularly interested in the effect of political trauma on the poet’s use of language. The anthology Against Forgetting was intended to collect the work of poets who had endured the impress of extremity during the twentieth century, whether through their engagements or force of circumstance. These experiences included warfare, military occupation, imprisonment, torture, forced exile, censorship, and house arrest. The anthology, composed of the work of one hundred and forty-five poets writing in English and translated from over thirty languages, begins with the Armenian Genocide and ends with the uprising of the pro-Democracy movement at Tiananmen Square. Although she was not guided in her selections by the political or ideological persuasions of the poets, Forché believes the sharing of painful experience to be radicalizing, returning the poet to an emphasis on community rather than the individual ego. In this she was strongly influenced by Terrence des Pres.

Forché is also influenced by her Slovak family background, particularly the life story of her grandmother, an immigrant whose family included a woman resistance fighter imprisoned during the Nazi occupation of former Czechoslovakia. Forché was raised Roman Catholic and religious themes are frequent in her work. Her fourth book of poems, Blue Hour, was released in 2003. Forthcoming books include a memoir, The Horse on Our Balcony (2010, HarperCollins), a book of essays (2011, HarperCollins) and a fifth collection of poems, In the Lateness of the World (HarperCollins).

Bibliography

- * Women in American Labor History, 1825-1935: An Annotated Bibliography (Michigan State University, 1972), with Martha Jane Soltow and Murray Massre

- * Gathering the Tribes (Yale University Press, 1976), ISBN 0300019831

- * History and Motivations of U.S. Involvement in the Control of the Peasant Movement in El Salvador: The Role of AIFLD in the Agrarian Reform Process, 1970-1980 (EPICA, 1980), with Philip Wheaton

- * The Country Between Us (Harper & Row, 1981), ISBN 0060149558

- * El Salvador: Work of Thirty Photographers (W.W. Norton, 1983), ISBN 0863160638

- * Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness (W.W. Norton, 1993), ISBN 0393033724 (ed.)

- * The Angel of History (HarperCollins, 1994), ISBN 0060170786

- * Writing Creative Nonfiction: Instruction and Insights from Teachers of the Associated Writing Programs (Story Press, 2001), ISBN 1884910505 (ed. with Philip Gerard)

- * Blue Hour (HarperCollins, 2003), ISBN 0060099127

James Michael Kacian, an American haiku poet, editor, publisher, and public speaker was born on July 26, 1953, in Worcester, Massachusetts, then adopted and raised in Gardner, Massachusetts. He has lived in London, Nashville, Bridgton (Maine) and now resides in Winchester, Virginia. Kacian wrote his first mainstream poems in his teens, and published them in small poetry magazines beginning in 1970. He also wrote, recorded, and sold songs during his time in Nashville in the 1980s. Upon his return to Virginia in 1985 he discovered English-language haiku, for which he is best known.

James Michael Kacian, an American haiku poet, editor, publisher, and public speaker was born on July 26, 1953, in Worcester, Massachusetts, then adopted and raised in Gardner, Massachusetts. He has lived in London, Nashville, Bridgton (Maine) and now resides in Winchester, Virginia. Kacian wrote his first mainstream poems in his teens, and published them in small poetry magazines beginning in 1970. He also wrote, recorded, and sold songs during his time in Nashville in the 1980s. Upon his return to Virginia in 1985 he discovered English-language haiku, for which he is best known.

Dušan “Charles” Simić (born 9 May 1938) is a Serbian-American poet, and was co-Poetry Editor of the Paris Review. He was appointed the fifteenth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 2007.

Dušan “Charles” Simić (born 9 May 1938) is a Serbian-American poet, and was co-Poetry Editor of the Paris Review. He was appointed the fifteenth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 2007.

Alice Ann Munro ( born 10 July 1931) is a Canadian short-story writer, winner of the 2009 Man Booker International Prize for her lifetime body of work, and three-time winner of Canada’s Governor General’s Award for fiction. Generally regarded to be one of the world’s foremost writers of fiction, her stories focus on the human condition and relationships through the lens of daily life. While the locus of Munro’s fiction is Southwestern Ontario, her reputation as a short-story writer is international. Her “accessible, moving stories” explore human complexities in a seemingly effortless style. Munro’s writing has established her as “one of our greatest contemporary writers of fiction,” or, as Cynthia Ozick put it, “our Chekhov.”

Alice Ann Munro ( born 10 July 1931) is a Canadian short-story writer, winner of the 2009 Man Booker International Prize for her lifetime body of work, and three-time winner of Canada’s Governor General’s Award for fiction. Generally regarded to be one of the world’s foremost writers of fiction, her stories focus on the human condition and relationships through the lens of daily life. While the locus of Munro’s fiction is Southwestern Ontario, her reputation as a short-story writer is international. Her “accessible, moving stories” explore human complexities in a seemingly effortless style. Munro’s writing has established her as “one of our greatest contemporary writers of fiction,” or, as Cynthia Ozick put it, “our Chekhov.”

Recent Comments