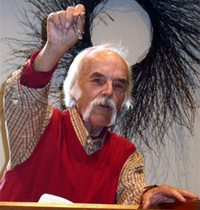

St. Patrick at work at Gordon Lodge

NOTES from the UNDERGROUND No.182 | May 22, 2009

IN MEMORIAM, A FINAL TOAST TO THE WORLD’S GREATEST BARTENDER:

ST. PATRICK

by

Norbert Blei

In the end, St. Pat died pretty much the way he always lived—chasing that rainbow, that horse to the finish line. Only this time the odds were against him, age…poor health. And both the dream and the man finally died.

I’ll keep this short and add some excerpts from a chapter devoted to him which appeared in the third book of the Door Trilogy series. There’s a fourth book in the works. The final end of St. Pat will be found there. You can bet on it.

For now, let’s leave it like this: St. Pat crossed the finish line in Ohio last Friday, May 22, at the age of 81. If you knew the man, be assured he went out in style, grace, never at a loss for words, a smile on his face, with a ticket to ride on a long shot: Win, Place, or Show.

I haven’t read this piece since I wrote it over 20 years ago. I was amazed to discover how it ended–then and now.

Excerpts from

“St. Pat—and the End of the Rainbow”

Ah, for the breath of some blarney in a confused world of too many serious people trying to make too much sense out of everything. And nobody serves it up better (straight or on the rocks) then St. Patrick (alias James Patrick Fagan), Door County’s father to fallen souls, comforter (Southern or name you own nirvana) to troubled and untroubled hearts, Grand Marnier Master of Ceremonious Nights on the Door. (He tells of one forgettable night in his particular parish—the Top Deck of Gordon Lodge—when Grand Marnier flowed in such abundance that the Saint himself seemed baffled the next morning to find all the money slots of the cash drawer filled with it.) A man of many miracles. Wine to water was easy. But a cold cash drawer to Grand Marnier? Only an un-canonized Irish bartending saint could do.

Smile, Patrick! (Which is his winning way with the world.) He’s always smiling. (Or will be again, he promises, as soon as he gets his teeth fixed. He’s made a deal at the bar with some dentist. And you can bet your own teeth that St. Pat will soon be smiling with his new ivories—high-tailing it to Chicago, to Florida, or back to Door—while the dentist will be wondering who took the big bite out of him.

He’s a rolling stone, a ramblin’ man, the veritable “condition” our elders warned we might someday find ourselves in if we weren’t thrifty and well-behaved: a man without a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out. Smile, Paddy! Your horse is in the money.

There he goes, snapping those fingers in front of your face, brushing that long wisp of black hair over his balding pate, flashing that smile, giving you the Irish: “I’m tellin’ ya! Listen to me!” Giving you his beautiful bullshit.

Dressed, always, partially in green, baggy pants hanging from his rather thin frame, his hands constantly fishing his front pockets for a cigarette lighter or cash. One of the biggest tippers of all time, he carries a crumpled wad of bills (his life savings) in his front pocket, pulling off fives and singles for the “help”—with whom he of course identifies. A single cup of coffee from a smiling waitress (say Denise Braun at Al’s) will net her at least a three dollar tip. Maybe five. The last of the big-time spenders. Definitely a city-type.

He loves children. Loves people. Loves charitable causes. More than a bit of the Irish in him. He’s definitely the guy who would give you the shirt off his own back. “I will donate to anything, as long as it’s a worthy cause.” Rich or poor, he’s been both. Sometimes in a matter of minutes.

Bless the fast horses, St. Patrick. And the long shots.

Of course there’s a bit of the con-artist about him. (Aren’t we all a little envious of the fast talker?) It’s the language of the survivor who must live by his mouth. A hustling life doesn’t come easy. And there are times the piper must be paid. Even moments of sadness around those black, beetle-brows and bright blue eyes of St. Pat. Bartender! Maybe just one more before I have another.

“Say,” he says to an attractive lady smoker, “Weren’t you at Gordon’s the other night? The Top Deck? Would you have an extra cigarette? Thanks. Did I hear Chicago?” he swings around toward another table. “Isn’t it beautiful here, this county? Stop by at the Top Deck for a drink.” He begins passing out brochures from his back pocket.

I manage to hustle him off one morning to a quiet picnic bench along the Lake Michigan shore for a few hours—definitely a fish out of water. St. Pat without a crowd—without strangers, without a bar to sit at or set up—is a drinker, a smoker doing cold turkey.

“Sit down, St. Pat, damn it! This is Mother Nature all around you. What you keep telling the tourists you love about Door County. Yes, I know, all it needs is a racetrack,” I tell him. Talk, say something!

But he’s befuddled. Frustrated. He’s on his last Camel cigarette. (Not that it matters what kind of cigarette at this point.) Already his flickering eyes are scanning the horizon, the empty picnic benches, the empty beach. St. Pat in exile. Who’s he gonna hit up for a smoke in this place?

“Don’t you have one cigarette on you?” he pleads. “Not one …’uckin’ cigarette? It’s OK. I’m alright. I’m telling you . . .” And he does.

His father, Peter Fagan, from County Cork, a railroad man, died when Patrick was 10. His mother, Mary Lenehan, lived to the age of 93. Cleveland, Ohio is home—was home. He doesn’t really have a home, except for summers in Door County, tending bar.

He lives in a suitcase, owns no car, no house, no bank account. Nothing. Zero. Zilch. Zip. A man on the run.

“I travel with a deck of cards, ten pairs of socks, five pairs of shorts, and a rosary,” he laughs. “I’m not afraid to go into any city without a dime in my pocket. I’ve never missed a meal. Willing to do anything. I’m at ease with the Vanderbilts and the bums on the street because I speak the international language—friendship. Money is nothing to me. Money is a kernel of corn the Indians used to trade. I’ve seen wealth in action—many, many unhappy people screaming over a few measly dollars.”

Like many a good Irish lad, Jimmie Fagan seemed destined for the priesthood. That was his mother’s wish. “And there I was, on my way to Sacred Heart Seminary in Detroit. I left Holy Name High at the age of 14.1 worked nights on the railroad as a switchman. But I loved horses too. I worked days at the racetrack—Ascot Park in Akron, galloping the horses. Exercise boy. And then the family threw this party for me, sending me off to the seminary to be a priest. I had the black suit and the sheets and everything. And I was on the bus, talking to the driver, and we passed a racetrack in Maumee, Ohio . . . 1945. And the driver knew! He knew! Let me out of here! And I was off to the races. Because of my Irish mother, I didn’t go home for three years. Nor did I talk to her.

“I knocked around racetracks all over the country, and I noticed how dressed-up the jockey agents were. Agents are solicitors for mounts for a jockey. You gotta know breeding, be an excellent handicapper—which I was. It looked like dream street. The end of the rainbow! (St. Pat is standing now, hollering, rummaging through his pockets for a cigarette. I offer him a pipe—no good. The stub of my cigar—no good.) I’m alright! I’m alright! Let’s go. I gotta sell some more damn tickets!

“Where was I? The end of the rainbow! But little did I know, little did I know” (lots of drama in his wonderful Irish storytelling voice, lots of facial expression) “that the jockey agents were mostly broke! But anyway, I moved out of the bam and into a hotel. And I met a jockey, Eric Guerin, who went on to win every major stake in the country. And I was with him for 14, 15 years. Hialeah, New York, the Jersey . . .

“Goddamn it! Doesn’t anyone have a cigarette? It’s alright.

“I learned about the fast life—booze, broads, the good times. A beautiful woman in every city. Nice ladies. Mucho women. But they weren’t promiscuous women. I made them that way!

“At one point my jockey couldn’t make the weight anymore. And I felt I never really wanted another jockey because we were such good friends. So I went to Palm Beach, Florida on a vacation and I met a guy, Joe O’Hara, who said he needed a bartender. I lied and told him I could do it. He put me into the service area that night. And all of a sudden here come 10 professional cocktail waitresses, and they all started ordering drinks I never knew existed. I said, PLEASE, GET ME OUT OF HERE!

“O’Hara asked me if I could make a Scotch and water. Hell, that’s what I drink! Anyway, he told me he would teach me how to tend bar, but I could not participate in tips, or salary, till I learned how. After 10 days, he came in one night all dressed up with his wife. It was a Saturday night. And he said, “You’re on your own!”

“I was in my 30’s then. I had black beautiful hair and white teeth. The women would just roll all over me. I love all women, and no particular woman will ever catch my eye. Marriage, no. Still … I love kids. I would have loved to have some kids.”

“Some of the famous customers I served . . . Bishop Sheen, a CC Manhattan with a water back. Jack Kennedy. I trembled when he came in. Dewar’s White Label Scotch on the rocks. Always some joke. The latest joke. Jackie Gleason and his beautiful wife would sit at the bar and make my day by ordering champagne, $75 a bottle, I was very low key with him because I was always nervous when he came in. And he always shook my hand when he left—with a crisp C-note for the Saint!

“The name! The name! Saint Patrick. How I got my name. There was a theft at the hotel of towels and sheets—I mean, more than usual. And Mr. MacArthur hired some detectives and a lie detector expert to case the hotel. One day he came up to me and said: ‘Patrick, you really are a saint.’ I was clean. The detectives had watched me, cleared me. Little did he know I have a 6th sense about strange people watching me!”

. “…one time this couple comes in and tells me about their beautiful resort in Door County, Wisconsin. Phil and Curly Gordon, I snickered to myself and said, ‘Wisconsin? Door County, Wisconsin?’ After the Gordons left, a real elderly bartender, Eddie O’Brien, told me that Door County was exactly like Ireland. The next year, 1971 ,I arrived. By bus, of course, I don’t have my own car. I keep my life savings in my pocket.

“I said to myself :’This is it, brother. The end of the rainbow for me. ‘And I’ve been happy, happy, happy ever since.

“Phil Gordon to me was a genius. At first I didn’t realize why he had separated the bar from the dining room, but everything he did was right. He even had the windows of the Top Deck set a certain way so we can catch a double sunset. Genius! The man was a genius!

” One night he came into the Top Deck, I poured him his usual Scotch on the rocks, and he said: “You better have one yourself. He probably knew I already had 20. The people from Milwaukee always bought the bartender a drink. They didn’t tip—but they bought you a drink. Sure! Always. It’s an inside joke among the bartenders. We call them the F.B.I, agents because all they ever leave are fingerprints. And you must drink it right there. You can’t tell them you’ll have it later. They insist you have it in front of them. You see what Milwaukee’s done to me? I love ’em.

“Many, many a night Phil Gordon and I sat alone in the Deck and drank till 7 in the morning. We discusses the world at large. He liked all the philosophers, and I liked Tolstoy—because he made love to every woman in sight! I loved Phil, Curly, the whole family.

“Where’s a cigarette, a cigarette?” He’s pacing the beach now, a determined man. “A butt, a butt. Isn’t there one stinking butt on this beach? See how clean this goddam county is! Can’t even find a cigarette butt here!

“My kind of bar is a one-man operation. It’s hard to work with other bartenders. I take charge of the room. I can see any argument starting in any part of the room. I eject them. No crabby people. Strictly happy people. I try to generate love in the room.

“The Top Deck is a finger-touch control bar. Phil created it. The view is the mostspectacular view in Door County. But the magic about the bar is the customers. Not just the hotel people, but the people in the county. And Chicago’s Northside. My favorites. Because they’re outgoing, likeable people, and it’s easy to make them laugh. If crabby people come in, it’s a personal challenge to me to make them laugh and enjoy themselves—because they’ll come back and tell their friends!

When the doors to Gordon Lodge and the Top Deck swing shut in mid-October, St. Pat is on the move once more. Time to pack the suitcase again. Time to board the bus. Take the act back on the road.

“Then it’s my vacation time,” he smiles. “After the season at Gordon’s and before coming back up here from Florida, I always hit Chicago. With my savings from both resorts in my pocket, I become a bartender’s delight. I check in at the Continental Hotel off Michigan Ave. All the staff, the help there know me. Gratuities flow like buttermilk. I can get any girl I want in Chicago by saying three magic words: Here’s a hundred. I high roll it!

“After about 7 days—the semi-annual collect call goes out to the good father for the non-transferable bus ticket to either Florida or Door County.”

The “good father”? “The Rev. H.J. Fagan, pastor of the Immaculate Conception Catholic Church in Madison, Ohio. My brother. I call him Harry. He’s a top fund- raiser like myself. Once in a while he tries to hit me up for something. And he talks almost as fast as I do.”

We’re heading back to town now. Lunch at Al’s. A pack of cigarettes for St. Pat. (“Camels! The humper. Five packs a day!”) He must open the Top Deck in a couple of hours, but from now until then he’s pushing tickets for the Roast. As for the origin of the Bartenders’ Roast…”…this will be the biggest Roast ever. Al Johnson—my kind of guy. I was dumb till I seen him work. I’ve copied him. He is the top restaurateur. That’s why I respect him—because I only like winners. His people all love him. Love him, are you kidding? How’s this when I help to introduce him: ‘Al Johnson’s driving up to Door County, and this beautiful hitchhiker stops him. ‘Say,’ she says, ‘Do you go all the way?’ And Al drove her to Washington Island.’ ”

Later, that afternoon/night at Gordon’s, the conversation continues:

“A bartender must be a good listener,” he continues. “He must be able to listen to five different conversations at one time and blend them all into one so that you have 10 happy people at the same time. Never discuss religion or politics. Memory! You must remember their drinks. And sometimes you must remember to forget who they are drinking with! And for my beautiful, beautiful ladies, I give them titles: Countess, Princess, Queen. Because I really believe that’s what they are.”

The banter, the blarney, the bull—the magic of St. Patrick. It’s irresistible. As addictive as alcohol. A double-whammy: St. Pat and a drink of your choice. He’s working some out-of-town customers at the bar now, charming them all. One guy, who finds St. Pat’s hyper-delivery too incredible for words, finally asks: “How long can you keep this up? How long do you work?” “All afternoon, all night,” St. Pat answers. “Six days a week.” The guy shakes his head in wonder, and keeps drinking.

It’s the Irish in him, I suggest.

“Just like my mother,” counters St. Pat. “She was a fast talker. A politico. Banging doors. Dragging me along with her. Talk to the people. It’s our heritage. You’re brought up to be proud of being an Irishman. I’ve worn green all my life. Of course the Irish build castles in the air. They’re all daydreamers. It’s a magical feeling. The outgoing personality . . . sometimes overpowering to some people. I can’t explain it. A lot of dopers ask me what I take. I tell them I’m on a natural high. And I love it, this way. I’m like this from the moment I wake up. I’m down very rarely. Only for 30 seconds. Then I lift my bootstraps right away, and I’m off to the races! It’s another hill to climb—make that a mountain.”

And what’s the biggest tip St. Pat ever received?

“$300 one night here in the Deck. They guy smiled and said he finally met a bartender who, could high roll it. His tab came to about $600. He gave me a thousand—keep the change.

In and out the door many times, St. Pat reflects: “I’ve been fired from Gordon Lodge 36 times—and rehired the next morning.” And if by chance some day he awakes to find the door to the Top Deck closed to him for good? “I’ll come back and be a doorman at Al’s. Just to open those doors for the people, I’ll pay him a $100 a week! Or I’ll shine shoes. I’ve got a lot of pride, but I’d do anything to be here. I’m going to live to be 93 just like my fast-talking Irish mother. The man upstairs told me. So get used to me.”

Though there was some speculation that St. Pat might be a goner for good after last year’s season, he is on the mend. Amen. Off the hootch, since last year’s celebrated Door County Bar Hopping Trolley Ride (organized by who else but the Saint himself . . . purely for the benefit of good spirits).

“I tell you, if I drank one, I had 50 J.B.’s and water. I fell asleep…They thought I was dead. / thought l was dead! I don’t want to talk about health!

“The saddest time of the year coming up for me. The end of the season. The last two nights here. I miss the customers. Even the ones I don’t like! People drift in and out, ‘So long, St. Pat. See you next year.’ Next year! I mean, who knows? Who knows?”

One version of the end, according to St. Patrick: “We will all be greeted by a green police unit, for Sheriff Baldy will have St. Peter’s job. And for those who behaved— a clear path on clouds 42 and 57. I prefer 57.

“I will definitely be buried in Door County, and I hope the good people here will hold an Irish Wake Roast for me—with me in attendance, of course—and provide a shaded lot in a Catholic cemetery.

“And on my tombstone have it writ: He Carried His Life Savings In His Front Pocket To The End.”

[From DOOR TO DOOR, Ellis Press, 1985.]

Note: St. Pat requested that his ashes be scattered in Door County. There will be a gathering of friends this fall.

the writer, Coyote, Lovta DuMore X (the writer’s secretary) and St. Patrick, drawing by Charles Peterson—from CHRONICLES OF A RURAL JOURNALIST IN AMERICA, by Norbert Blei, Samizdat Press, 1990.

The recent piece on Henry Denander (see archives,

The recent piece on Henry Denander (see archives,  The book finally came together in a work called I THOUGHT YOU WERE THE PICTURE. Cross+Roads Press published it in 1996. Only the 6th chapbook to come off the press (presently at work on #32). Staple binding. Eight bucks. (A special signed and numbered edition of just a few more bucks where he did an original drawing in each book.) A total run of 500 copies. All of them—long gone.

The book finally came together in a work called I THOUGHT YOU WERE THE PICTURE. Cross+Roads Press published it in 1996. Only the 6th chapbook to come off the press (presently at work on #32). Staple binding. Eight bucks. (A special signed and numbered edition of just a few more bucks where he did an original drawing in each book.) A total run of 500 copies. All of them—long gone.

In her first collection Standing Female Nude (1985) she often uses the voices of outsiders, for example in the poems ‘Education for Leisure’ and ‘Dear Norman’. Her next collection Feminine Gospels (2002) continues this vein, showing an increased interest in long narrative poems, accessible in style and often surreal in their imagery. Her 2005 publication, Rapture (2005), is a series of intimate poems charting the course of a love affair, for which she won the £10,000 T.S. Eliot Prize. In 2007 she published a poetry collection for children entitled The Hat. Many British students read her work as set texts while studying for English Literature at GCSE and A-level, as she became part of the syllabus in England and Wales in 1994. The poet has characterized her poetry using a simile: “Like the sand and the oyster, it’s a creative irritant. In each poem, I’m trying to reveal a truth, so it can’t have a fictional beginning.” Online copies of her poems are extremely rare but her poem dedicated to U A Fanthorpe, Premonitions, is available online courtesy of The Guardian. And some further poems are now presented by the Daily Mirror.

In her first collection Standing Female Nude (1985) she often uses the voices of outsiders, for example in the poems ‘Education for Leisure’ and ‘Dear Norman’. Her next collection Feminine Gospels (2002) continues this vein, showing an increased interest in long narrative poems, accessible in style and often surreal in their imagery. Her 2005 publication, Rapture (2005), is a series of intimate poems charting the course of a love affair, for which she won the £10,000 T.S. Eliot Prize. In 2007 she published a poetry collection for children entitled The Hat. Many British students read her work as set texts while studying for English Literature at GCSE and A-level, as she became part of the syllabus in England and Wales in 1994. The poet has characterized her poetry using a simile: “Like the sand and the oyster, it’s a creative irritant. In each poem, I’m trying to reveal a truth, so it can’t have a fictional beginning.” Online copies of her poems are extremely rare but her poem dedicated to U A Fanthorpe, Premonitions, is available online courtesy of The Guardian. And some further poems are now presented by the Daily Mirror. Duffy was almost appointed Poet Laureate in 1999 (after the death of previous Laureate Ted Hughes), but lost out on the position to Andrew Motion. According to the Sunday Times Downing Street sources stated unofficially that Prime Minister Tony Blair was “worried about having a homosexual poet laureate because of how it might play in middle England”. Duffy later claimed that she would not have accepted the laureateship anyway, saying in an interview with the Guardian newspaper that “I will not write a poem for Edward and Sophie. No self-respecting poet should have to.” She says she regards Andrew Motion as a friend and that the idea of a contest between them for the post was entirely invented by the newspapers. “I genuinely don’t think she even wanted to be poet laureate,”“The post can be a poisoned chalice. It is not a role I would wish on anyone – particularly not someone as forthright and uncompromising as Carol Ann.” said Peter Jay, Duffy’s former publisher. The Guardian has also stated that Duffy was reluctant to take up the role in 1999 as she was in a relationship at the time, and had a young daughter, so was reluctant to take up a position which would have put her so prominently in the public eye. Nevertheless, she was finally appointed to the position in May 2009, as successor to Andrew Motion.

Duffy was almost appointed Poet Laureate in 1999 (after the death of previous Laureate Ted Hughes), but lost out on the position to Andrew Motion. According to the Sunday Times Downing Street sources stated unofficially that Prime Minister Tony Blair was “worried about having a homosexual poet laureate because of how it might play in middle England”. Duffy later claimed that she would not have accepted the laureateship anyway, saying in an interview with the Guardian newspaper that “I will not write a poem for Edward and Sophie. No self-respecting poet should have to.” She says she regards Andrew Motion as a friend and that the idea of a contest between them for the post was entirely invented by the newspapers. “I genuinely don’t think she even wanted to be poet laureate,”“The post can be a poisoned chalice. It is not a role I would wish on anyone – particularly not someone as forthright and uncompromising as Carol Ann.” said Peter Jay, Duffy’s former publisher. The Guardian has also stated that Duffy was reluctant to take up the role in 1999 as she was in a relationship at the time, and had a young daughter, so was reluctant to take up a position which would have put her so prominently in the public eye. Nevertheless, she was finally appointed to the position in May 2009, as successor to Andrew Motion.

Recent Comments