NOTES from the UNDERGROUND No. 157 | October 18, 2008

Recipes & Writing in Autumn

by

Norbert Blei

When the bright days and brisk nights of October arrive I think of the glowing feast of color, the warmth of food. Autumn leaves, squash soup. My book shelves beckon after midnight…an appetite for words…something to read and eat. (“The “Literature of Food”—another from a list of writing courses I will probably never develop or ever teach. But oh how nourishing.)

Soup alone. A warm bowl cradled in the hands, aroma rising in steam.

“Poet-chef.” What could be more complete?

Pomiane…I think of him. Consider some lines written on the back of one of his books:

As a dietician and a professor at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, Edouard de Pomiane (1875-1964) acquired a profound knowledge of the nutritive and medical values of food, and of its history. He made a study of the chemistry of cooking and explained the reasons behind the methods, enabling his followers to understand just why certain ingredients behaved as they did, to avoid culinary mistakes, wherever humanly possible, and to put things right where, in spite of care, they had gone wrong. Yet his attitude was light-hearted, his delight in good food infectious, and his approach to cookery charmingly carefree. A certain dish, he warned, was disastrous to the figure – ‘but one can always start slimming tomorrow!’ All his life he enjoyed cooking for his family and friends and regarded it as an art with which to express the warmth of human kindness. But he was a very practical cook with many demands on his time and he well understood the need to produce delicious dishes with the minimum amount of fuss, and was also fully aware of the necessity of balancing the housekeeping budget. Dedicated users of the first edition will welcome its return with great pleasure: devotees of de Pomiane’s Cooking In Ten Minutes will turn with delight and with confidence to this wider selection of recipes: new readers have a real treat in store.

As a dietician and a professor at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, Edouard de Pomiane (1875-1964) acquired a profound knowledge of the nutritive and medical values of food, and of its history. He made a study of the chemistry of cooking and explained the reasons behind the methods, enabling his followers to understand just why certain ingredients behaved as they did, to avoid culinary mistakes, wherever humanly possible, and to put things right where, in spite of care, they had gone wrong. Yet his attitude was light-hearted, his delight in good food infectious, and his approach to cookery charmingly carefree. A certain dish, he warned, was disastrous to the figure – ‘but one can always start slimming tomorrow!’ All his life he enjoyed cooking for his family and friends and regarded it as an art with which to express the warmth of human kindness. But he was a very practical cook with many demands on his time and he well understood the need to produce delicious dishes with the minimum amount of fuss, and was also fully aware of the necessity of balancing the housekeeping budget. Dedicated users of the first edition will welcome its return with great pleasure: devotees of de Pomiane’s Cooking In Ten Minutes will turn with delight and with confidence to this wider selection of recipes: new readers have a real treat in store.

I move next to “The King of Chefs,” Georges Auguste Escoffier. A little biography, some anecdotes about Escoffier (1846-1935):

One evening at the turn of the century, the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) came to dine at London’s Savoy and was startled by an offering near the top of the menu. It read: “Cuisses de Nymphes a Vaurore—Nymphs’ Thighs alt Dawn.” Intrigued, the prince nibbled at them, then called for the chef and demanded to know what he was eating. Frogs’ legs, announced the chef. (In this case poached in a white-wine court bouillon, steeped in an aromatic cream sauce, seasoned with paprika, tinted gold, covered by a champagne aspic and served cold.) Aristocratic English circles in those days considered as vulgar an animal as the frog a gastronomic monstrosity, but the prince’s verdict was: delicious. From that time Nymphs’ Thighs became a familiar tidbit in the best London restaurants, and the chef became known as the man who taught Englishmen to eat frogs. The High Cost of Salmon. He was, of course, a Frenchman. He was also a genius. His name: Georges Auguste Escoffier (1846-1935), renowned as “the king of chefs and the chef of kings.” He plied King George V with variations of one of the monarch’s favorite dishes, cream cheese. He fed Kaiser Wilhelm salmon steamed in champagne. “How can I repay you?” the Kaiser asked. “Give us back Alsace-Lorraine,” the Frenchman replied. [Source: TIME]

One evening at the turn of the century, the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) came to dine at London’s Savoy and was startled by an offering near the top of the menu. It read: “Cuisses de Nymphes a Vaurore—Nymphs’ Thighs alt Dawn.” Intrigued, the prince nibbled at them, then called for the chef and demanded to know what he was eating. Frogs’ legs, announced the chef. (In this case poached in a white-wine court bouillon, steeped in an aromatic cream sauce, seasoned with paprika, tinted gold, covered by a champagne aspic and served cold.) Aristocratic English circles in those days considered as vulgar an animal as the frog a gastronomic monstrosity, but the prince’s verdict was: delicious. From that time Nymphs’ Thighs became a familiar tidbit in the best London restaurants, and the chef became known as the man who taught Englishmen to eat frogs. The High Cost of Salmon. He was, of course, a Frenchman. He was also a genius. His name: Georges Auguste Escoffier (1846-1935), renowned as “the king of chefs and the chef of kings.” He plied King George V with variations of one of the monarch’s favorite dishes, cream cheese. He fed Kaiser Wilhelm salmon steamed in champagne. “How can I repay you?” the Kaiser asked. “Give us back Alsace-Lorraine,” the Frenchman replied. [Source: TIME]

Literature, indeed. Stories. Drama. History. Humor. And of course, poetry.

Ah, there she is. One of my American favorites in the mix of literature and food: M.F.K. Fisher. A pen or a wooden spoon in hand? Perhaps both. Among her many works, fiction and nonfiction, her classic: HOW TO COOK A WOLF. Always a good read. Basic survival, words &food; sugar & salt. And never to forget: “It is impossible to think of any good meal, no matter how plain or elegant, without soup or bread in it”–M.F.K. Fisher. (Read her short stories sometime.)

Finally, how can I forget my experience with the famous Hungarian chef in Chicago, Chef Louis Szathmary, back in the 1970’s? (See CHI TOWN). A man of power, performance, brilliance, humor, history, literature. An artist who spoke and wrote in the true language of food.

“I see no reason why the artists in the kitchen who are creating our daily bread should not be treated academically the way other artists are. To be a good chef, a good culinarian is to be an artist, and a scientist. Our skills are the perfect combination of creative, visual, and performing arts at once.” — Chef Louie

October—cool, sunny days, warm, tasty soup. Here’s Pomiane, writer and chef:

Edouard de Pomiane

SOUPS

Pumpkin Soup

Pumpkin Soup

Sometimes I feel that I am very old. When I consider all the changes which have occurred over the long years since I was a child, I feel like a stranger even in the Paris where I was born. The din of the traffic has put the street songs to flight. One is no longer woken by the cry of the groundsel sellers. The raucous song of the oyster man no longer reminds one that it is Sunday which must be celebrated round the family table with a feast of oysters.

The shops have changed too. Only the windows of the butter, egg and cheese shops have kept their character, and on the pavement just beside the door one can still admire the giant pumpkin with gaping sides squatting on its wooden stool and seeming to say to passers-by, “Why not make some pumpkin soup ? And you will need some milk for it too. Come inside and buy some.”

Certainly in my young days there was no wooden stool. The pumpkin was balanced on top of two other uncut pump¬kins which were the rendezvous of all the dogs in the neighborhood who stopped there … for a moment or two. The stool is a triumph of modern hygiene.

If you are making pumpkin soup, buy a slice weighing about 1 lb. You will need 1 1/2 pints of milk and 2 ozs of rice as well.

Peel the pumpkin and cut the flesh into small pieces. Put them into a saucepan with a tumblerful of water. Boil for about 15 minutes, then mash the pumpkin to a puree. Add the milk and bring it to the boil. Now pour in the rice and season with salt and pepper. Simmer for 25 minutes.

At this moment the rice should be just cooked. Adjust the seasoning to your taste adding, if you like it, a pinch of caster sugar. I prefer a sprinkling of freshly-milled black pepper.

[from COOKING WITH POMIANE, Faber Paperbacks, 1976]

Edouard Alexandre de Pomiane, sometimes Edouard Pozerski (20 April 1875 – 26 January 1964) was a French scientist, radio broadcaster and food writer. His parents emigrated from Poland in 1863, changed their name from Pozerski to de Pomiane, and became French citizens. De Pomiane worked as a physician at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, where he gave Félix d’Herelle a place to work on bacteriophages.

His best known works to have been translated into English are Cooking in Ten Minutes and Cooking with Pomiane. His writing was remarkable in its time for its directness (he frequently uses a strange second-person voice, telling you—the reader—what you are seeing and smelling as you follow a recipe) and for his general disdain for “traditional” elaborate French cuisine. He travelled widely and quite a few of his recipes are from abroad. His recipes often take pains to demystify cooking by explaining the chemical processes at work.

Books

- * French cooking in ten minutes : or, Adapting to the rhythm of modern life (1930) ISBN 0-571-13599-4

- * Cooking with Pomiane ISBN 0-340-59937-5

Georges Auguste Escoffier (28 October 1846–12 February 1935) was a French chef, restaurateur and culinary writer who popularized and updated traditional French cooking methods. He is a near-legendary figure among chefs and gourmets, and was one of the most important leaders in the development of modern French cuisine. Much of Escoffier’s technique was based on that of Antoine Carême, one of the codifiers of French Haute cuisine, but Escoffier’s achievement was to simplify and modernize Carême’s elaborate and ornate style.

Alongside the recipes he recorded and invented, another of Escoffier’s contributions to cooking was to elevate it to the status of a respected profession, introducing organized discipline to his kitchens. He organized his kitchens by the brigade de cuisine system, with each section run by a chef de partie. He also replaced the practice of service à la française (serving all dishes at once) with service à la russe (serving each dish in the order printed on the menu).

Escoffier published Le Guide Culinaire, which is still used as a major reference work, both in the form of a cookbook and a textbook on cooking.

Publications

- * Le Traité sur L’art de Travailler les Fleurs en Cire (Treatise on the Art of Working with Wax Flowers) (1886)

- * Le Guide Culinaire (1903)

- * Les Fleurs en Cire (new edition, 1910)

- * Le Carnet d’Epicure (A Gourmet’s Notebook) (1911)

- * Le Livre des Menus (Recipe Book) (1912)

- * L’Aide-memoire Culinaire (1919)

- * Le Riz (Rice) (1927)

- * La Morue (Cod) (1929)

- * Ma Cuisine (1934)

- * 2000 French Recipes (1965, Translated to English by Marion Howells) ISBN 1-85051-694-4

- * Memories of My Life (1996, from his own life souvenirs published by his grandson in 1985 and translated into English by L. Escoffier, his great granddaughter in-law), ISBN 0-471-28803-9

- * Les Tresors Culinaires de la France (2002, collected by L. Escoffier from the original Carnet d’Epicure)

Louis I. Szathmary, born June 2, 1919, Budapest, Hungary. Graduate, University of Budapest, Masters degree in Journalism; Ph.D., Psychology, 1944. During the war he briefly attended the Hungarian cooks school while in the Hungarian Army. One of his responsibilities as a psychologist was to write the instruction manuals for the troops regarding field artillery as well as any issues of field cookery and proper procedures relating to military rations. Immigrated to United States, 1951. Married Sadako Tanino, of Los Angeles, CA, 1960. Died in Chicago October 4,1996.

1989-1996 Founder/Curator Emeritus Culinary Archives & Museum at Johnson & Wales University (The world’s largest culinary museum. His contribution was over 400,000 pieces from ancient times to the present.) 1989-1996 Chef Laureate, Johnson & Wales University, Providence, RI 1964-1996 President, Louis Szathmary Associates, Food System Designers and Management Consultants, Chicago 1962-1989 Executive Vice-President, Lou D’Or, Inc., ChicagoOwner-chef, “The Bakery” Restaurant, Chicago 1959-1964 Manager, New Product Development, Armour and Company, Chicago 1958-1959 Plant Superintendent, Reddi Fox Caterers, Darien, CT 1955-1958 Executive Chef, Mutual Broadcasting System, New York 1951-1955 Chef, New England Province, Jesuit Order, Norwalk, CT

Author And Columnist

- * “The Chef’s Secret Cook Book”

- * “Sears Gourmet Cooking Forum”

- * “American Gastronomy”

- * “The New Chef’s Secret Cook Book,”

- * “The Bakery Restaurant Cookbook.”

- * Editor, 15-Volume “Cookery Americana,”

- * “Antique American Cook Books.”

- * The Iowa Szathmary Culinary Arts Series; Nelson Algren’s “America Eats.”

- * Countless books in Hungarian, including several books of poetry.

Over the years, Szathmary has written for the “Skyline,” (a near north newspaper), the Chicago Daily News, Chicago Sun-Times, Houston Chronicle, and “Inside Lincoln Park.” He has been contributing editor of “Chef” Magazine, published by Talcott Publishing Company. He has authored more than 500 articles in food service, scientific and educational journals, among them the Cornell Hotel Quarterly, Food Service Magazine, Cooking for Profit, American Wine & Food, Food & Wine Society, Travel/Holiday Magazine, Hungarian Heritage Review, In This Issue, Biblio Magazine, as well as and several Hungarian publications in the U.S., Canada, and Europe.

Over some 50 years, he participated in more than 1,150 television and radio broadcasts, local and national, including Mike Douglas, Dinah Shore, Phil Donahue, Kathryn Crosby, Oprah Winfrey, the Pat Sajak Show, “Good Morning America,” “PM Magazine,” “Kup’s Show,” “ABC Network News,” and NBC “Go.”

Lectures and demonstrations at more than 30 colleges, trade and professional associations, including: Cornell, Michigan State, Florida International University, Roosevelt University, Tirton College, Kendall College, Washburn Trade School, California Polytech, Boston University, Oklahoma State, University of Missouri, Penn State, University of Nevada-Las Vegas, Oxford University, England, Dartmouth College, Harvard University, University of Chicago, Purdue University, University of Michigan, Culinary Institute of America (New Haven & Hyde Park), University of Southern California, Grand Rapids Junior College, and Johnson & Wales University. Also, The Young Presidents Organization, National Restaurant Association, National Frozen Foods Association, National Festival of American Foods and Cookery, American Culinary Federation, American Academy of Chefs, Honorable Order of Golden Toque, and The Food Service Executives Association.

From 1992 to the present, among the many places he lectured at were the Cosmos Club in Washington, D.C., National Space Society’s “Treasures of Discovery,” the 11th International Space Development Conference, Penn State, University of Iowa, Johnson & Wales University, and Oxford University in England.

Appeared in numerous broadcast commercials and print advertisements, sponsored by Sears, Charmglow, Chicken Delight, Tum’s, Lipton Tea, Lea & Perrins, Christian Dior, Jim Beam, Armour, American Express, Stewart’s Coffee and many others.

Member of: Society of Professional Management Consultants; Council on Hotel, Restaurant and Institutional Education; Board of Governors, National Space Society; Board of Directors, Chicago Academy of Sciences; Screen Actors Guild; American Federation of Television and Radio Artists; International Association of Cooking Schools; Les Amis d’Escoffier; American Culinary Federation; American Academy of Chefs; Honorable Order of the Golden Toque; Chefs de Cuisine Association; Master Chefs Institute; International P.E.N. Club; International Food Wine & Travel Writers Association; International Wine & Food Society of London; Caxton Club of Chicago; Cliff Dwellers Club of Chicago; Groiler Club of New York; Stephen Parmenius Foundation; and American Hungarian Cultural Association of Chicago.

It was at the 1974 American Culinary Federation convention in Cleveland, Ohio, when keynote speaker Chef Louis Szathmary declared that European governments honored their Executive Chefs, but that in America, chefs were officially listed in the same category as “domestics, dog walkers, chamber maids and butlers.” He called on the convention to change this official view and gave the first $500 to hire a professional lobbyist to achieve this goal. In January 1977, at the final Washington, D.C. meeting which included Department of Labor and American Culinary Federation officials, the listing of Executive Chef was advanced in the Dictionary of Official Titles from the “Services” category to the “Professional, Technical, and Managerial Occupations” category. America’s Executive Chefs were officially recognized as professionals!

Awards and Recognitions

- * Honorary Doctorate in Business – Lincoln College, Lincoln Illinois

- * Honorary Doctorate of Culinary Arts – Johnson & Wales University, 1990

- * 1996 appointed to Editorial Advisory Board of Biblio Magazine, The Magazine for Collectors of Books, Manuscripts, and Ephemera

- * Living Legend Silver Spoon Award – Food Arts Magazine, 1995

- * Living Legend – Illinois Restaurant Association, 1993

- * Living Legend – James Beard Foundation, 1995

- * Hotel Man of The Year – Penn State Hotel School, 1977

- * Lifetime Achievement Award – Jozsef Venesz Award from the Hungarian Chefs Association, Hungary, 1996. (The highest honor for a Hungarian chef for promoting Hungarian Cuisine internationally.)

- * Hall of Fame -Life Time Achievement Award, American Academy of Chefs, 1996

- * Chef Laureate – Johnson & Wales University, 1989

- * Outstanding Culinarian – Culinary Institute of America, l974

Works In Progress At The Time of His Death

- * “The Bakery Restaurant Catering Book”

- * Hungarian Cookbook (both in English and Hungarian)

- * “History of The First Stomach” a book to be based on his presidential autograph collection.

- * A Dutch television crew was to film a television special based on his collecting habits at the end of October.

- * A traveling Culinary Archives & Museum exhibit at the 81st International Hotel/Motel & Restaurant Show, November 9-12, l996 Jacob K. Javits Convention Center, New York City.

- * In April l997 he was to be awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Penn State Hotel Society.

- * At Johnson & Wales University, Chef Louis was working with the school’s Advancement Department on fund-raising efforts to build a permanent home for the Culinary Archives & Museum.

- * He also was planning to lecture to students in The Hospitality College and the College of Culinary Arts at Johnson & Wales in November.

- * After his retirement he devoted himself to working on culinary related exhibits at the Culinary Archives & Museum and traveling exhibits to such places as Oxford University, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, Gerald Ford Presidential Library, Villa Terra- Milwaukee, Clements Library University of Michigan, Dartmouth, San Francisco International Airport Museum, Cosmos Club, Roosevelt University, University of Chicago, University of California-Santa Barbara, Hungarian Embassy-Washington D.C., Hungarian Consulate-New York City, etc. etc.

- * Although he was a retired chef , he came out of retirement to cook for causes close to his heart: The International House of Rhode Island, American Institute of Wine & Food, James Beard Foundation, openings to his book exhibitions and a private dinner for his dear friend and CEO of McDonald’s Fred Turner.

- * His presidential culinary related autograph collection was to be featured on the upcoming PBS special series “Presidential Palate” featuring former White House Executive Chef Henry Haller.

- * On election night November 5, 1996 on TV Food Network News his presidential culinary related autograph collection is to be featured in a two- hour special with intermittent election updates — a first in television history.

Chef Louis Szathmary lectured to culinary and hospitalty students all over the world. He would emphasize why he felt it was important for industry leaders to take the time to lecture to the next generation of culinarians and hoteliers. His internationally renowned “The Bakery” Restaurant was located across the street from a funeral home. Chef often remarked that for 26 years he observed those who had passed on being taken in and out of the funeral home. He noted that when they left this world, they were not able to take any worldly possessions with them. After years of observing this he felt an obligation to pass on as much of his knowledge to students because he realized that, when he was gone, he would never have the opportunity to share it with anyone.

Upon his retirement, the administration at Johnson & Wales University, wanted to provide him a house to reside in Providence, Rhode Island. He absolutely refused, citing the funeral home.

The accomplishment he was the most proud of was that he lived among the students he loved, in a residence hall. Among students, he was more recognizable than than the President of the University. He was the only adult on campus who was not a member of the Residential Life Staff who lived in the dorms, “by choice.” He enjoyed eating in the cafeteria with the students, walking in the halls, riding the elevator, and even the 2:30 a.m. false fire alarms — including the evacuations while still in their pajamas.

He felt that the best discussions he had in his life, were the moments he shared with the students — out of a classroom, when he was just one of them.

Szathmaryism:

“I see no reason why the artists in the kitchen who are creating our daily bread should not be treated academically the way other artists are. To be a good chef, a good culinarian is to be an artist, and a scientist. Our skills are the perfect combination of creative, visual and performing arts at once.”

source

Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher (July 3, 1908 – June 22, 1992) was a prolific and well-respected writer, writing more than 20 books during her lifetime and also publishing two volumes of journals and correspondence shortly before her death in 1992. Her first book, Serve it Forth, was published in 1937. Her books deal primarily with food, considering it from many aspects: preparation, natural history, culture, and philosophy. Fisher believed that eating well was just one of the “arts of life” and explored the art of living as a secondary theme in her writing. Her style and pacing are noted elements of her short stories and essays.

Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher (July 3, 1908 – June 22, 1992) was a prolific and well-respected writer, writing more than 20 books during her lifetime and also publishing two volumes of journals and correspondence shortly before her death in 1992. Her first book, Serve it Forth, was published in 1937. Her books deal primarily with food, considering it from many aspects: preparation, natural history, culture, and philosophy. Fisher believed that eating well was just one of the “arts of life” and explored the art of living as a secondary theme in her writing. Her style and pacing are noted elements of her short stories and essays.

Fisher was born Mary Frances Kennedy in Albion, Michigan on July 3, 1908. In 1911, her father, Rex Kennedy, moved the family to Whittier, California to pursue a career in journalism. Although Whittier was primarily a Quaker community at that time, Mary Frances was brought up within the Episcopal Church.

While studying at the University of California in 1929, Fisher met her first husband, Alfred Young Fisher. The couple spent the first formative years of their marriage in Europe, primarily at the University of Dijon in France. At the time, Dijon was known as one of the major culinary centers of the world and this certainly had an impact on Fisher, who later went on to become one of the great culinary writers of the twentieth century.

In 1932, the couple returned from France to a country ravaged by the Great Depression. Having lived for years as students on a fixed stipend, they were wholly unprepared for the economic situation that faced them. Al got odd jobs cleaning out houses before finally landing a teaching job at Occidental College in Los Angeles. Fisher did her part teaching a few lessons at an all-girls’ school and working in a frame shop.

In addition to being an author, Fisher was an amateur sculptor working mostly in the realm of wood carving.

During the Fishers’ years in California, they formed a friendship with Dillwyn “Timmy” Parrish and his wife, Gigi. Later, in 1938, Fisher was to leave Alfred for Timmy, referred to as “Chexbres” in many of her books, named after the small Swiss village on Lake Geneva close to where they had lived. The second marriage, while passionate, was short. Only a year into the marriage, Parrish lost his leg due to a circulatory disease, and in 1941 took his own life. Fisher went on to be involved in a number of other turbulent romantic relationships with men and women.

Fisher bore two daughters. Anna, whose father Fisher refused to name, was born in 1943. Mary Kennedy was born in 1946, during Fisher’s marriage to Donald Friede, which lasted from 1945 to 1951.

After Parrish’s death, Fisher considered herself a “ghost” of a person, but went on to live a long and productive life, dying in California in 1992 at the age of 83. She had long suffered from Parkinson’s disease and arthritis, but lived the last twenty years of her life in “Last House,” a house built for her in one of California’s vineyards.

Books

- * Serve It Forth (1937)

- * Aix-en-Provence

- * Consider the Oyster (1941)

- * How to Cook a Wolf (1942)

- * The Gastronomical Me (1943)

- * Here Let Us Feast, A Book of Banquets (1946)

- * Not Now but Now (1947)

- * An Alphabet for Gourmets (1949)

- * The Physiology of Taste [translator] (1949)

- * The Art of Eating (1954)

- * A Cordial Water: A Garland of Odd & Old Receipts to Assuage the Ills of Man or Beast (1961)

- * The Story of Wine in California (1962)

- * Map of Another Town: A Memoir of Provence (1964)

- * Recipes: The Cooking of Provincial France (1968) [reprinted in 1969 as The Cooking of Provincial France]

- * With Bold Knife and Fork (1969)

- * Among Friends (1971)

- * A Considerable Town (1978)

- * Not a Station but a Place (1979)

- * As They Were (1982)

- * Sister Age (1983)

- * Spirits of the Valley (1985)

- * Fine Preserving: M.F.K. Fisher’s Annotated Edition of Catherine Plagemann’s Cookbook (1986)

- * Dubious Honors (1988)

- * The Boss Dog: A Story of Provence (1990)

- * Long Ago in France: The Years in Dijon (1991)

- * To Begin Again: Stories and Memoirs 1908-1929 (1992)

- * Stay Me, Oh Comfort Me: Journals and Stories 1933-1941 (1993)

- * Last House: Reflections, Dreams and Observations 1943-1991 (1995)

- * Aphorisms of Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin from His Work, The Physiology of Taste (1998)

- * From the Journals of M.F.K. Fisher (1999)

- * Two Kitches in Provence (1999)

- * Home Cooking: An Excerpt from a Letter to Eleanor Friede, December, 1970 (2000)

source

![]()

![]()

David Sedaris

David Sedaris

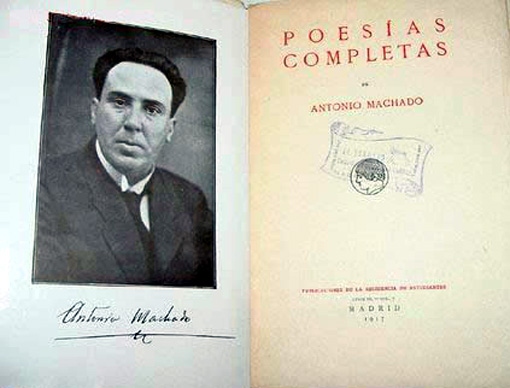

Antonio Cipriano José María y Francisco de Santa Ana Machado y Ruiz, known as Antonio Machado (July 26, 1875 – February 22, 1939) was a Spanish poet and one of the leading figures of the Spanish literary movement known as the Generation of ’98.

Antonio Cipriano José María y Francisco de Santa Ana Machado y Ruiz, known as Antonio Machado (July 26, 1875 – February 22, 1939) was a Spanish poet and one of the leading figures of the Spanish literary movement known as the Generation of ’98.

As a dietician and a professor at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, Edouard de Pomiane (1875-1964) acquired a profound knowledge of the nutritive and medical values of food, and of its history. He made a study of the chemistry of cooking and explained the reasons behind the methods, enabling his followers to understand just why certain ingredients behaved as they did, to avoid culinary mistakes, wherever humanly possible, and to put things right where, in spite of care, they had gone wrong. Yet his attitude was light-hearted, his delight in good food infectious, and his approach to cookery charmingly carefree. A certain dish, he warned, was disastrous to the figure – ‘but one can always start slimming tomorrow!’ All his life he enjoyed cooking for his family and friends and regarded it as an art with which to express the warmth of human kindness. But he was a very practical cook with many demands on his time and he well understood the need to produce delicious dishes with the minimum amount of fuss, and was also fully aware of the necessity of balancing the housekeeping budget. Dedicated users of the first edition will welcome its return with great pleasure: devotees of de Pomiane’s Cooking In Ten Minutes will turn with delight and with confidence to this wider selection of recipes: new readers have a real treat in store.

As a dietician and a professor at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, Edouard de Pomiane (1875-1964) acquired a profound knowledge of the nutritive and medical values of food, and of its history. He made a study of the chemistry of cooking and explained the reasons behind the methods, enabling his followers to understand just why certain ingredients behaved as they did, to avoid culinary mistakes, wherever humanly possible, and to put things right where, in spite of care, they had gone wrong. Yet his attitude was light-hearted, his delight in good food infectious, and his approach to cookery charmingly carefree. A certain dish, he warned, was disastrous to the figure – ‘but one can always start slimming tomorrow!’ All his life he enjoyed cooking for his family and friends and regarded it as an art with which to express the warmth of human kindness. But he was a very practical cook with many demands on his time and he well understood the need to produce delicious dishes with the minimum amount of fuss, and was also fully aware of the necessity of balancing the housekeeping budget. Dedicated users of the first edition will welcome its return with great pleasure: devotees of de Pomiane’s Cooking In Ten Minutes will turn with delight and with confidence to this wider selection of recipes: new readers have a real treat in store. One evening at the turn of the century, the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) came to dine at London’s Savoy and was startled by an offering near the top of the menu. It read: “Cuisses de Nymphes a Vaurore—Nymphs’ Thighs alt Dawn.” Intrigued, the prince nibbled at them, then called for the chef and demanded to know what he was eating. Frogs’ legs, announced the chef. (In this case poached in a white-wine court bouillon, steeped in an aromatic cream sauce, seasoned with paprika, tinted gold, covered by a champagne aspic and served cold.) Aristocratic English circles in those days considered as vulgar an animal as the frog a gastronomic monstrosity, but the prince’s verdict was: delicious. From that time Nymphs’ Thighs became a familiar tidbit in the best London restaurants, and the chef became known as the man who taught Englishmen to eat frogs. The High Cost of Salmon. He was, of course, a Frenchman. He was also a genius. His name: Georges Auguste Escoffier (1846-1935), renowned as “the king of chefs and the chef of kings.” He plied King George V with variations of one of the monarch’s favorite dishes, cream cheese. He fed Kaiser Wilhelm salmon steamed in champagne. “How can I repay you?” the Kaiser asked. “Give us back Alsace-Lorraine,” the Frenchman replied. [Source: TIME]

One evening at the turn of the century, the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) came to dine at London’s Savoy and was startled by an offering near the top of the menu. It read: “Cuisses de Nymphes a Vaurore—Nymphs’ Thighs alt Dawn.” Intrigued, the prince nibbled at them, then called for the chef and demanded to know what he was eating. Frogs’ legs, announced the chef. (In this case poached in a white-wine court bouillon, steeped in an aromatic cream sauce, seasoned with paprika, tinted gold, covered by a champagne aspic and served cold.) Aristocratic English circles in those days considered as vulgar an animal as the frog a gastronomic monstrosity, but the prince’s verdict was: delicious. From that time Nymphs’ Thighs became a familiar tidbit in the best London restaurants, and the chef became known as the man who taught Englishmen to eat frogs. The High Cost of Salmon. He was, of course, a Frenchman. He was also a genius. His name: Georges Auguste Escoffier (1846-1935), renowned as “the king of chefs and the chef of kings.” He plied King George V with variations of one of the monarch’s favorite dishes, cream cheese. He fed Kaiser Wilhelm salmon steamed in champagne. “How can I repay you?” the Kaiser asked. “Give us back Alsace-Lorraine,” the Frenchman replied. [Source: TIME]

Pumpkin Soup

Pumpkin Soup

Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher (July 3, 1908 – June 22, 1992) was a prolific and well-respected writer, writing more than 20 books during her lifetime and also publishing two volumes of journals and correspondence shortly before her death in 1992. Her first book, Serve it Forth, was published in 1937. Her books deal primarily with food, considering it from many aspects: preparation, natural history, culture, and philosophy. Fisher believed that eating well was just one of the “arts of life” and explored the art of living as a secondary theme in her writing. Her style and pacing are noted elements of her short stories and essays.

Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher (July 3, 1908 – June 22, 1992) was a prolific and well-respected writer, writing more than 20 books during her lifetime and also publishing two volumes of journals and correspondence shortly before her death in 1992. Her first book, Serve it Forth, was published in 1937. Her books deal primarily with food, considering it from many aspects: preparation, natural history, culture, and philosophy. Fisher believed that eating well was just one of the “arts of life” and explored the art of living as a secondary theme in her writing. Her style and pacing are noted elements of her short stories and essays.

Peter Matthiessen (born May 22, 1927, in New York City) is an American novelist and nonfiction writer and an environmental activist. Matthiessen’s work is known for its meticulous approach to research. He frequently focuses on American Indian issues and history, as in his detailed study of the Leonard Peltier case, In the Spirit of Crazy Horse.

Peter Matthiessen (born May 22, 1927, in New York City) is an American novelist and nonfiction writer and an environmental activist. Matthiessen’s work is known for its meticulous approach to research. He frequently focuses on American Indian issues and history, as in his detailed study of the Leonard Peltier case, In the Spirit of Crazy Horse.

Recent Comments