NOTES from the UNDERGROUND… No.138 | April 21, 2008

απολογία

[apologia…a speaking, in defense]

I.

preaefatio…

[something said before]

Somewhere in the living room near my chair, or by my bookshelves, or in a cloth briefcase, or in anyone of a number of large, heavy canvas tote bags I carry back and forth from house to coop each day, are the lives of others. Their writing lives. Perhaps yours as well, in my grip, on my mind, with every intention of ‘getting to it.’ Letters. Copies of manuscripts. Recently published books. Writers whose work, one way or another, falls into my hands…finds me. In a few cases, comes to me because I may have asked directly, or possibly said without thinking it through entirely: “Send me something sometime.” And occasionally work which is plainly dropped on me in a “Take-a-look-at-this-sometime-would-you?” kind of way. “Let me know…catch you later.”

Some of these people know me better than I know myself. Know my weakness for writing, for working writers, for particular writers consigned to a lifetime of writing for small, obscure presses. Know I have a hard time saying ‘no.’ Know my tendency to occasionally cry “Wolf!” too many times (“NO! Please! I CAN’T…I DON’T HAVE THE TIME!” ) eventually has neither sound or meaning. They suspect I will weaken. Will open the door, let them in. Expect/suspect this might lead to: Sympathy/understanding. A critique? Direction? Advice? Publication? A recommendation to another publisher?

(Only two paragraphs in—I don’t like the sound of this already. Where I seem to be coming from, where this piece seems to be headed. Excuses. ‘Poor me.’ Too patronizing, self-serving. Tell the truth!)

This is partly how it plays out in my head, when it’s always 3 o’clock in the morning in my living room after I’ve come into the house at the end of another writing day, after I’ve eaten supper, read the paper, watched the news, felt night coming on…when I would rather do anything but sleep, call it another day…when I would rather have another cup of coffee, read another page, another chapter of any of at least a dozen books I happen to be reading at the moment—turn off the light, put on headphones, listen to some music in the dark, listen to public radio (the BBC World News Overnight)…or when I remember how heavy that tote bag has become, how large the pile of books and manuscripts has grown in weeks or months, and I feel an obligation and an inclination to pull out somebody’s work already and see what’s there. And so put the light back on beside my chair, open an envelope (arranged in the order in which I received them) and finally attend to these other lives I have carried around with me far too long…reading into them till sleep overtakes me.

And sometimes (more than I realize), not up to any of this, (moody character that I am—that many writers are), unable to deal with any of it any more, (What do these people expect from me? Blood? Many of them my friends!)…angry with myself for allowing this to happen…angry with some of them for not realizing what I’m up against ever since I started a small press devoted to new writers without first books, veteran writers without a publisher…let alone all I am trying to do with my own writing)… I ignore my better instincts and turn away from all those screaming manuscripts and books…till Time passes, as it always does…till I climb out of whatever funk I’m in (from apathy to melancholia), till I get a better handle on “what I can do and what I can’t do.” Till I finally feel a little better about everything, come full circle. and the time is right, is now to open the envelopes, read what’s been there. Till I discover a manuscript or a book that lifts me out of the chair. A book to pass on to others. Or a manuscript I need to publish for the good of the author and others who may appreciate what I see in a new work.

I’m embarrassed to say that some manuscripts and books get away from me—for weeks, for months. Forever.( Forever?) Forever, Maybe. I’m saving manuscripts, books (him, her) for a time I can better concentrate, do the work and the writer the attention it deserves. Do something special—which, for whatever reason, doesn’t happen to be this moment. Maybe I need to do more background on the writer or the work. Maybe I want to be sure someone isn’t hustling me to do something for him/her, somebody else. Tit for tat. I HATE the payback game. And if I sniff it, will run as far away from it as possible—though I know this is the way things work—especially in the larger publishing circles.. Not that I’m pure. Not that I don’t wear my heart on my sleeve for more real, honest writers than anyone can imagine. Not that I haven’t occasionally done something for someone because at one point in my writing life I remember that person extending a hand to me or others. That happens. Often, deservedly so. And I’m willing to be called on it, defend it if I must. I would never show favor to anyone whose work I would not be proud to put on my own bookshelves.

So back to losing track of writers and their work. Back to the ‘maybes”…

Maybe, maybe…time passes…I lose sight, I lose interest—never intentionally. Something else/someone else comes knocking on my door in the middle of the night, or broad daylight, and I’m completely captivated by the stranger…a word, an image, a passage, a chapter, an idea for a book (often generated by me)—and I’m gone. Off again in another direction. This is the PLUS and MINUS of moving entirely too much by instinct. Too often, too many other things replace my original desires and intentions. I HATE when this happens—an unfulfilled promise to myself. Some manuscripts and books disappear from my hands without a trace, though rarely do I actually lose one. They’re always buried in some pile, misplaced in some divider of a cloth carrying-case, lurking in some recess of the working areas I inhabit, ready to accuse me in the dark: “Hey, what about me? When the hell you going to get around to me? Get back to me? Ain’t I as good as your latest attraction? That book of poems by some poet in Mongolia that nobody ever heard of? Man, you’re bustin’ me,..” But it doesn’t happen. (Immediately.) For the moment—which could last for (god to God) knows how long–I’m gone. I’ve lost sight of what I was intending to do, Silence on that front. ‘Disappeared’–me and the book, manuscript, writer I never got around to dealing with. Who can explain it? I can’t. But I’m trying…

“Ego Te Absolvo” … [I forgive you, you forgive me] …

There are many writers I would like to publish.. So many who deserve to be published. It’s a craze that comes upon some of us, somewhat ‘established’ as writers, who feel a need and an obligation to go beyond our own writing–publish others as well. We come and we go as publishers. Good and average. We think we see what needs to be done. Few of us last more than 10 years. Why us? Don’t we have enough of our own writing to do? Certainly. But then… I think of Ferlinghetti (City Lights), Marvin Malone (Wormwood Review–gone since the death of Malone), Curt Johnson (december press), Robert Bly (The Sixties Press),John Bennett (Hcolom Press),George Hitchcock (Kayak Press–gone), David Pichaske (Ellis Press, Spoon River Poetry Press, Plains Press), t.k. splake (The Vertin Press), Ron Offen (Free Lunch), and countless other independent presses/ publications out there trying their best to fill the void where larger, more commercial presses seldom look. There could be hundreds of us. Thousands, world-wide. Who knows? We barely know each other. And we are all beset, put-upon, tired, broke, angry at times…but still trying to get the job done. Looking forward to doing the next book. But who knows when?

The unreliable narrator has nothing over the unreliable publisher. I have disappointed many writers, I am sure. And will no doubt continue to do so as long as I remain a publisher. (“Ego te absolvo.”) So many demands, so many obstacles. So many ups and downs. And I have to remind myself every day: “This is a young man’s game. I don’t recognize that guy in the mirror, and that guy seems tired.” I used get angry as hell submitting work to publishers and not hearing from them for months, years later–or never hearing at all. Now I understand. In the worst of times, I’ve become one of them! Everyday I’m on the verge of writing THE END. I can’t do this anymore. Everyday I question the value of the effort. Everyday I reprimand myself (or others express disappointment in me): “Get back to your own work! Why are you wasting your time? You’ve done enough. Let someone else take up the cause.”

Every day I think of something or someone else I would like to print.

There’s no shortage of the kind of talent, the kind of book that interests me. That’s important, in defining yourself as a publisher, which too many writers don’t realize or comprehend. That’s the black hole of publishing for every writer trying to attract the attention of a publisher: ‘What does he want? Would my work interest him? Fat chance. But…maybe’.)

I wish I could publish a book I love or generate one from a writer I feel needs to be done, every month. There’s no end to this craziness. I keep adding names and ideas to my list. And I need to put a stop to it.

This is pretty much the late-night story. [STOP]–as they used to print to signal a pause, a break in Western Union telegraphic messages. All the ongoing projects and manuscripts that I do indeed both seek and solicit from writers on occasion (on my terms) for my own press, Cross+Roads Press. Projects that demand Time and Attention. All that plus all the newly published chapbooks, standard books, reprints, broadsides, CD’s, photographs, art work that come my way…that ceaseless beat to-be-published-and-acknowledged-to-be-published-and-acknowledged-to-be-published… [STOP] To attract SOMEBODY’S attention. [STOP] Manuscripts finding their way to me via websites, old friends, former students, e-mails: “What’s your snail-mail address? I want to send you a copy of my new book.” [STOP] All wanting and needing, what’s more deserving some attention, no matter …[STOP] I know that! [STOP] Furthermore, I really want to help. Really want to read your new book—possibly write something about it somewhere, if, if… I really, really do! I may even really want to publish a book of yours—sometime. But…But…[STOP]. There are so few people out there with any interest, desire, experience to take up the task, to lend an eye, an ear to other writers’ causes/efforts, be he/she a beginner, or a lifetime veteran of the word shop—365 days a year, below minimum wage, no vacation, no pension, no security, no health benefits, no guarantee of a happy marriage or relationship, no guarantee of success, or that God’s on your side or against you, no possibility you will find faith in anything but yourself–if you are lucky. And no chance/no doubt you will ever find anything more satisfying to do with your life than writing until you can no longer find the words to put together to make some kind of sense of what may appear, in the end, to have been an almost meaningless existence. [STOP] [STOP] [STOP]

II.

author, Agonistes

Wandering insatiably over the earth for years, greeting and taking leave over everything, I felt that my head was the globe and that a canary sat perched on the top of my mind, singing. –Nikos Kazantzakis

This is not what he set out to write. It never is

The writer is uncertain where the title, απολογία

came from.

He has carried this feeling around with him a long time, but the condition finally settled in him for good sometime last year.

Then, more recently, on a particularly bad day/night, the feeling “agonistes” attached itself. Followed, days later, by the “author, Agonistes.”

The writer has been wrestling with this matter…(scratch “wrestling”… write what you see inside. The truth of myth.) The Greek language appeared when “agonistes” came calling in the beginning, the very first line. (Stay with the Greek. Let it unravel…-you remember, what’s-her-name??? Yes, her.)

The writer’s struggle with the subject he is presently unraveling has been positively Sisyphean. (Not him again!) That’s the picture, though it came after agonistes—and apologia.

But what could be more beautiful than the Greek alphabet: απολογία ?

Words that float upon Homer’s wine-dark sea, glow in the rosy-fingered dawn.

Seeing is knowing (thinks the writer, attempting to shed the parenthentical, the artist within).…To truly see… is to truly love.

Slipping for the moment into first person (the writer explains): Once I lived awhile on a Greek island in the village of, ΛιnΔoε, on the island of Rhodos. What could be more beautiful than a Greek island in spring, red poppies on the hillsides, the blinding white village hovering above the Mediterranean, the dead, comfortably at home in their stone graves, smiling upon sea and sky …What could be more beautiful than the name of the village, ΛιnΔoε, in Greek, ‘pictured’ in print?

A time in my life (reflects the writer, first person) when Sisyphis was only a myth, the writing was everywhere before one’s eyes waiting to be plucked, put down on paper, caught live At dawn every day, the tiny white houses tumbled down to the sea in spreading light… old men with night lanterns, hovering over the water in colored wooden boats fished for octopus …the sun reaching up and down the hillside, women from everywhere in the world lying every which way on the beach inviting the fire to lick their bodies… the bare-breasted black-African woman in meditational pose…earth, air, sky, and water. Here we are gathered together. Xenos all, strangers/guests, hungering for light, starry-dark, moon-love, the shadow soul.

And oh, the music, the food, the wine, the talk, villagers and voyagers all with nowhere to go but where you found yourself each night,up and down the narrow cobblestone walks, congregating finally at Kosta’s dimly lit taverna with the barred windows open to the night, the old women in black, their faces pressed against the iron bars, badgering their drinking husbands to come home. Here, where you found yourself night after holy night, at Kosta’s near the domed church…here, denying ‘hereafter’ in story, laughter, desire. Lost-and-found souls of a book in progress that had no symbolism on the page, here where the story was lived beyond language, here where words inevitably failed because the living was always a better story than the telling.

When that journey ended, the writer returned relunctantly yet in some vague anticipation to the the house he abandoned in the rural, near a small lake. He was met at the door by what he remembered of himself once being there…some joy, a little sorrow, and much uncertainty. Was he beginning all over again or had something ended he had no way of knowing or expressing? He opened the door a crack, only to be met immediately by the familiar. That, plus a damp, mustiness filled the air. He stepped into the darkness, flicked on the light switch, but there was no light. He made his way to the cupoard above the sink, found some candles and lit them. There was a broken window near the kitchen table, torn curtains. Water on the floor. The smell of dead mice permeatied everything. He lit a smoke from the last pack of Turkish cigarettes he had purchased in the old country and sat in a wooden chair at the kitchen table till all the candles burned out. He remained there in the darkness for a long time, half awake till morning.

Weeks passed. He made-do. He was on his way back from and to somewhere. But it would take a while to figure out. He saw no one but an old neighbor down the road who helped make the house habitable, about as comfortable as he could stand it. He was determined not to require much.

He saw a boat for sale next to a neigbor’s barn one day and bought it. An old flat-bottom, metal row boat, used for duck hunting, the color of mediterranean blue. He painted ΛιnΔoε in black on both sides of the upturned bow and brushed-in a small orange sun above ΛιnΔoε on each side. He loved looking at the name, the painted sun against the blue. Looking out his kitchen window, he thought the boat seemed afloat on the edge of his green woods. He found a thick, braided rope in the woodshed, tied it around a heavy rock he dug out of the ground and fixed the other end of the line to the bow. Weeks passed. A whole season disappeared, the ΛιnΔoε remained afloat in hs eyes in the clearing in the woods. Sometimes, early mornings, warm afternoons, he would sit in the middle of the boat and smoke, read a book. He was reading Kazantzakis at the time. He carried him around in his back pocket ever since his life over there on the islands. He put to memory the old Cretan saying: “Return where you have failed,

leave where you have suceeded.”

The time came when he grew tired of his landlocked condition, backed up the pickup, grabbed the bow of the boat in both hands, pulled it a short distance over the ground, acrosss the crushed stone driveway, lifted and pushed the boat to the back of the truck and drove down to the water.

It was dusk. Still warm. Early autumn, the trees beginning to change color. Most of the visitors gone back to the city. Most of the locals concerned with daily survival. He rowed out to the middle of the small lake, pulling hard, feeling the movement of boat across the surface of the water in his hands, up his arms, coming to rest deep into both shoulders, the back of his neck. He was losing sight of things, leaving himself behind the further he rowed from shore. He was trying to find the old rhythms his boyhood body once knew.

The oars moved in and out of the water with barely a sound. He was taking his time, letting the boat find his way…just taking his time.The only thought in his head wasn’t so much a thought as a feeling, an image… the movement of water in his wake, watching the water drip back into the lake as he raised both oars simultaneously. He could feel his legs stretch deep into the bottom of the boat.

The whole motion might prompt a song, if he had a song in him. He had none. A gull cut a broken white line in the darkning sky above him as he attempted to stand up in the boat and drop the stone anchor into a place where he might find himself still, as still as any man could be on water, sitting in the middle of a boat, drifting here and there. Till the moon surprised him coming up over his shoulder, staring at him in the water. One moon. Shimmering. Two moons. Broken moons. Broken water. Moons spilling about.

The darker the night, the brighter the light on water, the smaller and more distant the moom, the more absent he felt in the silence.

The man in the moon.

Adrift.

Writing on water.

απολογία…he read into himself. Guilt heavy as stone tied in unforgiving knots.

agonistes…so much he’s left undone…still…

How many more stories must I tell? the writer asks himself.

So then what happens? Isn’t that the movement, the direction of all narratives? After his return? After the boat and the lake and the anchor and the moon and the words floating on water?

Nothing. He remembers. For sometime, nothing. For sometime coming back was like beginning. That was the best part. Like being alone on water, drifting. Waiting to find the words to tell. As in the beginning for any writer, where there is no other place to be but the place where the unimagined, inexpressible drifts somewhere about you and slowly reveals itself through you, through your head, into the blind, small warmth your mouth, the tasting of the tongue, then down into the throat, spreading across the chest, filtering through the heart, making its way down every path in the body, up the shoulder, down the arm, into the hand, down to the finger tips scribbling your tiny truths through a broken yellow pencil to be born and remembered on paper.

That was here, mine, once, he felt. He knew.

Every journey you make from everything holding you in place, freeing you, is an attempt to retrieve that.To get it back. Again. This time protect it. Keep it. Make it last.

But no anchor can hold that long enough.

Gradually you drift… and drift…and drift…ashore.

Where they are waiting for you.

[Excerpt–work in progress, ipgs/frmT/mid3-1/8]

![]()

![]()

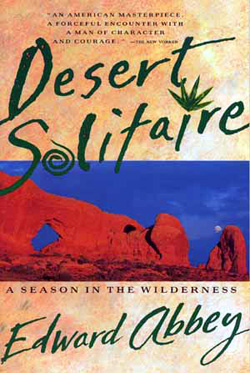

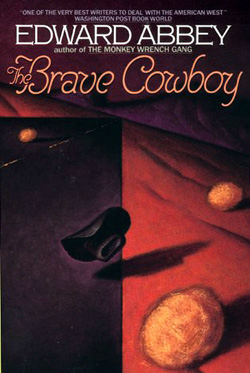

Good or bad, I like to think of these selected journal notes as potential essays, germinal essays, essays in a nutshell—one-liner or one-paragraph monographs—in which some vast formidable thesis, together with resounding conclusion, bristling from end to end with a full armament of apparatus scho-lasticus, is presented in nuclear form, leaving to the reader’s discernment, learning, logic, and intellectual energy its unfolding and full development. An isolate voice, crying from the desert. Vox clamantis in deserto is a role that few care to play, but I find pleasure in it. The voice crying from the desert, with its righteous assumption of enlightenment, tends to grate on the nerves of the multitude. But it is mine. I’ve had to learn to live within a constant blizzard of abuse from book reviewers, literary critics, newspaper columnists, letter writers, and fellow authors. But there are some rewards as well: The immense satisfaction, for example, of speaking out in plain blunt language on matters that the majority of American authors are too tired, timid, or temporizing even to allow themselves to think about. To challenge the taboo—that has always been a special delight of mine—and though all respectable and official and institutional voices condemn me, a million others think otherwise and continue to buy my books, paying my bills and financing my primrose path over the hill and down the far side to an early grave. Yes, it’s true by God, whatever I’ve accomplished as a writer, I’ve done on my own, without any encouragement from my ” fellow” authors and against first the indifference and then the resolute opposition of the guardians of our contemporary Kultur.

Good or bad, I like to think of these selected journal notes as potential essays, germinal essays, essays in a nutshell—one-liner or one-paragraph monographs—in which some vast formidable thesis, together with resounding conclusion, bristling from end to end with a full armament of apparatus scho-lasticus, is presented in nuclear form, leaving to the reader’s discernment, learning, logic, and intellectual energy its unfolding and full development. An isolate voice, crying from the desert. Vox clamantis in deserto is a role that few care to play, but I find pleasure in it. The voice crying from the desert, with its righteous assumption of enlightenment, tends to grate on the nerves of the multitude. But it is mine. I’ve had to learn to live within a constant blizzard of abuse from book reviewers, literary critics, newspaper columnists, letter writers, and fellow authors. But there are some rewards as well: The immense satisfaction, for example, of speaking out in plain blunt language on matters that the majority of American authors are too tired, timid, or temporizing even to allow themselves to think about. To challenge the taboo—that has always been a special delight of mine—and though all respectable and official and institutional voices condemn me, a million others think otherwise and continue to buy my books, paying my bills and financing my primrose path over the hill and down the far side to an early grave. Yes, it’s true by God, whatever I’ve accomplished as a writer, I’ve done on my own, without any encouragement from my ” fellow” authors and against first the indifference and then the resolute opposition of the guardians of our contemporary Kultur. The Deserto in the title, therefore, denotes not the regions of dry climate and low rainfall on our pillaged planet but, rather, the arid wastes of our contemporary techno-industrial greed-and-power culture; not the clean outback lands of sand, rock, cactus, buzzard, and scorpion, but, rather, the barren neon wilderness and asphalt jungle of the modern urbanized nightmare in which New Age man, eyes hooded, ears plugged, nerves drugged, cannot even get a decent night’s sleep. While the grumbling, eccentric Vox, though isolated, may speak—I suspect—for the desperations and aspirations of many. Of very many, deprived by circumstance of the opportunity to speak for themselves. Where the means of communication fall within the control of a tightly centralized monopoly, free speech becomes a meaningless gesture, a useless privilege. When and if the opportunity does come, one must make the most of it or betray both thy neighbors and thyself.

The Deserto in the title, therefore, denotes not the regions of dry climate and low rainfall on our pillaged planet but, rather, the arid wastes of our contemporary techno-industrial greed-and-power culture; not the clean outback lands of sand, rock, cactus, buzzard, and scorpion, but, rather, the barren neon wilderness and asphalt jungle of the modern urbanized nightmare in which New Age man, eyes hooded, ears plugged, nerves drugged, cannot even get a decent night’s sleep. While the grumbling, eccentric Vox, though isolated, may speak—I suspect—for the desperations and aspirations of many. Of very many, deprived by circumstance of the opportunity to speak for themselves. Where the means of communication fall within the control of a tightly centralized monopoly, free speech becomes a meaningless gesture, a useless privilege. When and if the opportunity does come, one must make the most of it or betray both thy neighbors and thyself.

Recent Comments