Poetry Dispatch No. 66 | April 21, 2006

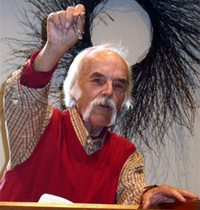

In celebration of Earth Day/weekend, 2006…one of America’s most beloved poets, from a collection of poems, essays and photographs put together last year in honor and celebration of Stanley Kunitz, (100) master gardener–plants and words. Norbert Blei

Turning the Soil by Stanley Kunitz

WHY is the act of cultivating so compelling?

All my life, the garden has been a great teacher in everything I cherish. As a child, I dreamed of a world that was loving, that was open to all kinds of experience, where there was no prejudice, no hatred, no fear. The garden was a world that depended on care and nourishment. And it was an interplay of forces; as much as I responded to the garden, the garden, in turn, responded to my touch, my presence.

The garden isn’t, at its best, designed for admiration or praise; it leads to an appreciation of the natural universe, and to a meditation on the connection between the self and the rest of the natural universe. And this can come not only from the single flower in its extravagant beauty, but in the consideration of the harmony established among all aspects of the garden’s form.

The garden is a domestication of the wild, taking what can be random, and, to a degree, ordering it so that it is not merely a transference from the wild, but still retains the elements that make each plant shine in its natural habitat.

In the beginning, a garden holds infinite possibilities. What sense of its nature, or its kingdom, is it going to convey? It represents a selection, not only of whatever individual plants we consider to be beautiful, but also a synthesis that creates a new kind of beauty, that of a complex and multiple world. What you plant in your garden reflects your own sensibility, your concept of beauty, your sense of form. Every true garden is an imaginative construct, after all.

I think of gardening as an extension of one’s own being, something as deeply personal and intimate as writing a poem. The difference is that the garden is alive and it is created to endure just the way a human being comes into the world and lives, suffers, enjoys, and is mortal. The lifespan of a flowering plant can be so short, so abbreviated by the changing of the seasons, it seems to be a compressed parable of the human experience.

The garden is, in a sense, the cosmos in miniature, a condensation of the world that is open to your senses. It doesn’t end at the limits of your own parcel of land, or your own state, or your own nation. Every cultivated plot of ground is symbolic of the surprises and ramifications of life itself in all its varied forms, including the human.

Is the cycle any easier to accept in the garden than in a human life? Both of them are hard to take! In both cases there is a sense not only of obligation, but of devotion. You might say, as well, that the garden is a metaphor for the poems you write in a lifetime and give to the world in the hope that these poems you have lived through will be equivalent to the flower that takes root in the soil and becomes part of the landscape. If you’re lucky, that happens with some of the poems you create, while others pass the way of so many plants you set into the garden, or grow from seed: they emerge and give pleasure for a season and then vanish.

from THE WILD BRAID, A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden, Norton, 2005

Leave a comment