Poetry Dispatch No. 5 | September 10, 2005

Before the Flood by W.S. Merwin

Why did he promise me

that we would build ourselves

an ark all by ourselves

out in back of the house

on New York Avenue

in Union City New Jersey

to the singing of the streetcars

after the story

of Noah whom nobody

believed about the waters

that would rise over everything

when I told my father

I wanted us to build

an ark of our own there

in the back yard under

the kitchen could we do that

he told me that we could

I want to I said and will we

he promised me that we would

why did he promise that

I wanted us to start then

nobody will believe us

I said that we are building

an ark because the rains

are coming and that was true

nobody ever believed

we would build an ark there

nobody would believe

that the waters were coming.

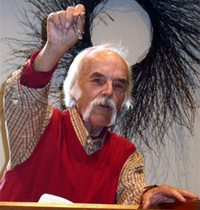

William Stanley Merwin (born September 30, 1927 in New York City) is one of the most influential American poets of the latter 20th century.

Merwin made a name for himself as an anti-war poet during the 1960’s. Later, he would evolve toward mythological themes and develop a unique prosody characterized by indirect narration and the absence of punctuation. In the 80’s and 90’s, Merwin’s interest in Buddhist philosophy and deep ecology also influenced his writing. He continues to write prolifically, though he also dedicates significant time to the restoration of rainforests in Hawaii, the state where he lives.

Merwin has received many honors, including a Pulitzer Prize and a Tanning Prize, one of the highest honors bestowed by the Academy of American Poets.

Merwin grew up in Union City, New Jersey and Scranton, Pennsylvania. He graduated from Princeton University in 1948. His father was a Presbyterian minister. ‘I started writing hymns for my father as soon as I could write at all’, Merwin has said. While at Princeton, he studied writing with John Berryman and R. P. Blackmur, to whom his fifth book, The Moving Target (1963), was later dedicated. Merwin spent a postgraduate year at Princeton studying Romance languages, an interest that would lead, eventually, to his much-admired work as a translator of Latin, Spanish, and French poetry.

Merwin travelled in France, Spain, and England. He settled in Majorca in 1950 as a tutor to Robert Graves’s son. Graves, with his interest in mythology, would become a primary influence on young Merwin. Moving to London in 1951, Merwin made his living as a translator for several years. In America, his first book of poems won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Award for 1952, selected by W. H. Auden, who remarked in his introduction on the young poet’s technical virtuosity. That volume, A Mask for Janus, is immensely formal, neoclassical in style. For the next decade Merwin would regularly publish collections of intensely wrought, brightly imagistic poems that recalled the poetry of Wallace Stevens as well as Robert Graves and other influences. After his graduation from Princeton, Merwin has never been associated with a writing program or university. He has lived all over the world, and he now lives in Haiku, Hawaii.

Merwin travelled in France, Spain, and England. He settled in Majorca in 1950 as a tutor to Robert Graves’s son. Graves, with his interest in mythology, would become a primary influence on young Merwin. Moving to London in 1951, Merwin made his living as a translator for several years. In America, his first book of poems won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Award for 1952, selected by W. H. Auden, who remarked in his introduction on the young poet’s technical virtuosity. That volume, A Mask for Janus, is immensely formal, neoclassical in style. For the next decade Merwin would regularly publish collections of intensely wrought, brightly imagistic poems that recalled the poetry of Wallace Stevens as well as Robert Graves and other influences. After his graduation from Princeton, Merwin has never been associated with a writing program or university. He has lived all over the world, and he now lives in Haiku, Hawaii.

At a Union City (NJ) council meeting in early March 2006, historian Kathie Pontus formally requested that the city of Union City honor Merwin, who was scheduled to be in New Jersey to accept the National Book Award for his latest poetry collection (ISBN 1-55659-218-3) called Migration. Pontus asked the board that a street naming be held on April 22, 2006 for Merwin, who when contacted for the event, stated that he was “nostalgic about Union City, and moved that it remembered him, and would love to return home to receive this honor.”

At a Union City (NJ) council meeting in early March 2006, historian Kathie Pontus formally requested that the city of Union City honor Merwin, who was scheduled to be in New Jersey to accept the National Book Award for his latest poetry collection (ISBN 1-55659-218-3) called Migration. Pontus asked the board that a street naming be held on April 22, 2006 for Merwin, who when contacted for the event, stated that he was “nostalgic about Union City, and moved that it remembered him, and would love to return home to receive this honor.”

In 1952 Merwin’s first book of poetry, A Mask for Janus, was published in the Yale Younger Poets Series. W. H. Auden selected the work for that distinction. Later, in 1971 Auden and Merwin would exchange harsh words in the pages of The New York Review of Books. Merwin had published a feature, On Being Awarded the Pulitzer Prize in the June 3, 1971 issue of The New York Review of Books that announced his objection to the Vietnam War and that he was donating his prize money. Auden responded in a letter entitled Saying No that appeared in the July 1, 1971 issue stating that the Pulitzer Prize jury was not a political body with any ties to the American foreign policy.

From 1956 to 1957 Merwin was also playwright-in-residence at the Poet’s Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts; he became poetry editor at The Nation in 1962. Besides being a prolific poet (he has published over fifteen volumes of his works) he is also a respected translator of Spanish, French, Italian and Latin poetry, including Dante’s Purgatorio.

Merwin is probably best known for his poetry about the Vietnam War, and can be included among the canon of Vietnam War-era poets which includes such luminaries as Robert Bly, Adrienne Rich, Denise Levertov, Robert Lowell, Allen Ginsberg and Yusef Komunyakaa. In 1998, Merwin wrote Folding Cliffs: A Narrative, an ambitious novel-in-verse about Hawaiian history and legend.

Merwin is probably best known for his poetry about the Vietnam War, and can be included among the canon of Vietnam War-era poets which includes such luminaries as Robert Bly, Adrienne Rich, Denise Levertov, Robert Lowell, Allen Ginsberg and Yusef Komunyakaa. In 1998, Merwin wrote Folding Cliffs: A Narrative, an ambitious novel-in-verse about Hawaiian history and legend.

Merwin’s early subjects were frequently tied to mythological or legendary themes, while many of the poems featured animals, which were treated as emblems in the manner of William Blake. A volume called The Drunk in the Furnace (1960) marked a change for Merwin, in that he began to write in a much more autobiographical way. The title-poem is about Orpheus, seen as an old drunk. ‘Where he gets his spirits / it’s a mystery’, Merwin writes; ‘But the stuff keeps him musical’. Another powerful poem of this period is ‘Odysseus’, which reworks the traditional theme in a way that plays off poems by Stevens and Graves on the same topic.

In the 1960s Merwin began to experiment boldly with metrical irregularity. His poems became much less tidy and controlled. He played with the forms of indirect narration typical of this period, a self-conscious experimentation explained in an essay called ‘On Open Form‘ (1969). The Lice (1967) and The Carrier of Ladders (1970) (which won a Pulitzer Prize) remain his most influential volumes. These poems often used legendary subjects (as in ‘The Hydra’ or ‘The Judgment of Paris’) to explore highly personal themes.

In Merwin’s later volumes, such as The Compass Flower (1977), Opening the Hand (1983), and The Rain in the Trees (1988), one sees him transforming earlier themes in fresh ways, developing an almost Zen-like indirection. His latest poems are densely imagistic, dream-like, and full of praise for the natural world. He has lived in Hawaii since the 1970s, and one sees the influence of this tropical landscape everywhere in the recent poems, though the landscape remains emblematic and personal. Migration won the 2005 National Book Award for poetry.

Poetry

- * The First Four Books of Poems, 1975, 2000

- * A Mask for Janus, 1952- Awarded the Yale Younger Poets Prize, 1952

- * The Dancing Bears, 1954

- * Green with Beasts, 1956

- * The Drunk in the Furnace, 1960

- * The Second Four Books of Poems, 1993

- * The Moving Target, 1963

- * The Lice, 1967

- * The Carrier of Ladders, 1970- Awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, 1971

- * Writings to an Unfinished Accompnaiment, 1973

- * The Compass Flower, 1977

- * Finding the Islands, 1982

- * Opening the Hand, 1983

- * The Rain in the Trees, 1988

- * Selected Poems, 1988

- * Travels, 1993

- * The Vixen, 1996

- * Flower & Hand, 1997

- * The Folding Cliffs: A Narrative, 1998

- * The River Sound, 1999

- * The Pupil, 2001

- * Migration: New & Selected Poems, 2005

- * Present Company, 2005

Prose

- * The Miner’s Pale Children, 1970

- * Houses and Travellers, 1977

- * Regions of Memory

- * Unframed Originals: Recollections, 1982

- * The Lost Uplands: Stories of Southwest France, 1992

- * The Mays of Ventadorn, 2002

- * The Ends of the Earth, 2004

Translations

- * The Poem of the Cid, 1959

- * The Satires of Persius, 1960

- * Spanish Ballads, 1961

- * Lazarillo de Tormes, 1962

- * The Song of Roland, 1963

- * Selected Translations, 1948 – 1968, 1968

- * Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair, Poems by Pablo Neruda, 1969

- * Products of the Perfected Civilization, Selected Writings of Chamfort, 1969

- * Voices, Poems of Antonio Porchia, 1969, 1988, 2003

- * Transparence of the World, Poems by Jean Follain, 1969, 2003

- * Asian Figures, 1973

- * Osip Mandelstam: Selected Poems (with Clarence Brown), 1974

- * Euripedes’ Iphigeneia at Aulis (with George E. Dimock, Jr.), 1978

- * Selected Translations, 1968-1978, 1979

- * Four French Plays, 1985

- * From the Spanish Morning, 1985

- * Vertical Poetry, Poems by Roberto Juarroz, 1988

- * Sun at Midnight, Poems by Musō Soseki (with Soiku Shigematsu), 1989

- * Pieces of Shadow: Selected Poems of Jaime Sabines, 1996

- * East Window: The Asian Translations, 1998

- * Purgatorio from The Divine Comedy of Dante, 2000

- * Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, 2005

- * Summer Doorways: A Memoir, 2005

“Life all around me here in the village:

“Life all around me here in the village: He published Spoon River Anthology in 1915 under a pseudonym. He was worried it would have an effect on his law practice, and he was right to worry. The book was considered very scandalous at the time, but it became a best-seller. It went through 70 printings, and it allowed Masters to retire from his law practice. The people in the towns that he had grown up in were angry at him for decades. It took more than 50 years before the town where he went to high school was able to put Spoon River Anthology in the town library. (source: Writer’s Almanac)

He published Spoon River Anthology in 1915 under a pseudonym. He was worried it would have an effect on his law practice, and he was right to worry. The book was considered very scandalous at the time, but it became a best-seller. It went through 70 printings, and it allowed Masters to retire from his law practice. The people in the towns that he had grown up in were angry at him for decades. It took more than 50 years before the town where he went to high school was able to put Spoon River Anthology in the town library. (source: Writer’s Almanac)

Though he never matched the success of his Spoon River Anthology, Masters was a prolific writer of diverse works. He published several other volumes of poems including Book of Verses in 1898, Songs and Sonnets in 1910, The Great Valley in 1916, Song and Satires in 1916, The Open Sea in 1921, The New Spoon River in 1924, Lee in 1926, Jack Kelso in 1928, Lichee Nuts in 1930, Gettysburg, Manila, Acoma in 1930, Godbey, sequel to Jack Kelso in 1931, The Serpent in the Wilderness in 1933, Richmond in 1934, Invisible Landscapes in 1935, The Golden Fleece of California in 1936, Poems of People in 1936, The New World in 1937, More People in 1939, Illinois Poems in 1941, and Along the Illinois in 1942.

Though he never matched the success of his Spoon River Anthology, Masters was a prolific writer of diverse works. He published several other volumes of poems including Book of Verses in 1898, Songs and Sonnets in 1910, The Great Valley in 1916, Song and Satires in 1916, The Open Sea in 1921, The New Spoon River in 1924, Lee in 1926, Jack Kelso in 1928, Lichee Nuts in 1930, Gettysburg, Manila, Acoma in 1930, Godbey, sequel to Jack Kelso in 1931, The Serpent in the Wilderness in 1933, Richmond in 1934, Invisible Landscapes in 1935, The Golden Fleece of California in 1936, Poems of People in 1936, The New World in 1937, More People in 1939, Illinois Poems in 1941, and Along the Illinois in 1942.

Recent Comments