NOTES from the UNDERGROUND… No.140 | April 26, 2008

Earth Day Week, April 2008:

ED ABBEY

This concludes the ‘Literary Interpretation & Celebrations” of EARTH WEEK, 2008.

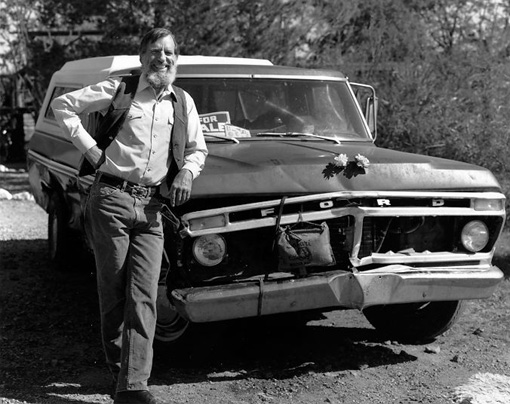

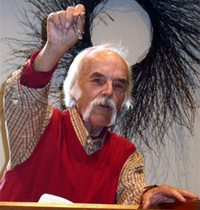

And who would be a stronger closer than the profane, pugnacious, problematic, scoundrel, sage, protector of the desert-mind, arch-enemy of the developer, the state, the status-quo, the late great Ed Abbey? (Buried in an unmarked grave somewhere in the American desert, the coyotes still feasting on his hardy bones—as he so desired.)

Best to let old Ed speak for himself here, though I could easily fill pages on what he meant/means to me personally. Just what an all-around ‘good guy’ he was to so many writers who, for whatever reason, found themselves in tune with his voice: Vox Clamantis in Deserto.

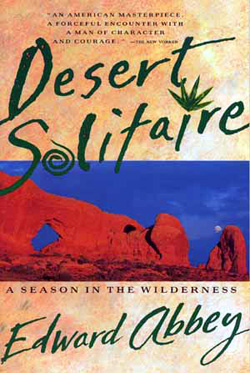

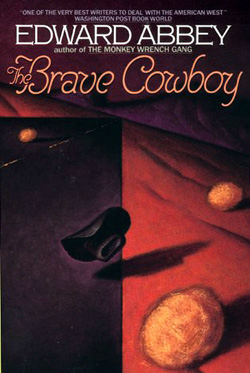

If you’ve never read him—start anywhere. But begin with Abbey’s own WALDEN POND, set in the dry Southwest, an American Classic of our time: DESERT SOLITAIRE.

The two excerpts below, “An Introduction” and “On Nature” are taken from his small but beautiful book, A VOICE CRYING IN THE WILDERNESS, Notes from a Secret Journal, St. Martin’s Press, 1989. Norbert Blei

![]()

An Introduction

It is with considerable diffidence and in the spirit of true humility which only a modern American writer can summon to the page so easily that I hereby offer this pretentious and artistically crafted little volume to the literary public. For years, I have been threatening that public—my readers—such as it is, with the detonation of a Fat Masterpiece. This book, readers, you will be relieved to learn, is not that book. My Vox is not fat, not masterly, not even a piece, but a deliberate collocation of fragments.

Most of the statements in the above paragraph are false. Not all of them.

The above statement is false.

In truth, I’m happy to see my Vox emerge from its shell, and cannot imagine any pretext for an apology. (A cheap paperback edition will follow in due time.) The shell, in this case, consists of a private journal I’ve been keeping, fairly faithfully, since 1948; a journal now twenty-one volumes long, and this chick, the bird or book, is simply a collection of fragments from that twenty-one-year-old personal record.

The fragments, or notes, were obviously not -chosen at random but with an eye to propositions and declarations that say something provocative in a minimum number of words. I’ve always been an admirer of the epigram and the aphoristic style—from Montaigne: “It is good to be born in a depraved time; for, compared to others, you gain a reputation for virtue at a small cost.” From Schopenhauer: ”Style is the physiognomy of the mind,” to Samuel Johnson: “Of all forms of wealth, intelligence at least seems fairly distributed; for no man complains of a lack of it.” Back to Schopenhauer: ” A pessimist is an optimist in full possession of the facts.” And on to Ambrose Bierce:” Love is a disease for which marriage is the perfect cure.” And George Santayana: ” For good or ill I am an ignorant man, almost a poet.” And finally, Aristotle: ” Melancholy men, of all others, are the most witty.” Some of my favorite books, such as Thoreau’s W olden, can be read as a mosaic of epigrams.

Herewith, I try my hand at it, making no claims at wit or wisdom, but hoping nonetheless (in secret) that within this paper bin the reader may discover a few nuggets of genuine gold, or of that which glitters even better: fool’s gold.

Some of these notes have appeared, in altered form, in previous books of mine, floating along in a flood of earnest prose. Others may be unconscious plagiarisms from the great and dead (never steal from the living and mediocre), ideas absorbed in my reading so long ago that I’ve made them mine and forgotten the source. If so, the author would appreciate hearing from readers on this point. (Be kind.)

Good or bad, I like to think of these selected journal notes as potential essays, germinal essays, essays in a nutshell—one-liner or one-paragraph monographs—in which some vast formidable thesis, together with resounding conclusion, bristling from end to end with a full armament of apparatus scho-lasticus, is presented in nuclear form, leaving to the reader’s discernment, learning, logic, and intellectual energy its unfolding and full development. An isolate voice, crying from the desert. Vox clamantis in deserto is a role that few care to play, but I find pleasure in it. The voice crying from the desert, with its righteous assumption of enlightenment, tends to grate on the nerves of the multitude. But it is mine. I’ve had to learn to live within a constant blizzard of abuse from book reviewers, literary critics, newspaper columnists, letter writers, and fellow authors. But there are some rewards as well: The immense satisfaction, for example, of speaking out in plain blunt language on matters that the majority of American authors are too tired, timid, or temporizing even to allow themselves to think about. To challenge the taboo—that has always been a special delight of mine—and though all respectable and official and institutional voices condemn me, a million others think otherwise and continue to buy my books, paying my bills and financing my primrose path over the hill and down the far side to an early grave. Yes, it’s true by God, whatever I’ve accomplished as a writer, I’ve done on my own, without any encouragement from my ” fellow” authors and against first the indifference and then the resolute opposition of the guardians of our contemporary Kultur.

Good or bad, I like to think of these selected journal notes as potential essays, germinal essays, essays in a nutshell—one-liner or one-paragraph monographs—in which some vast formidable thesis, together with resounding conclusion, bristling from end to end with a full armament of apparatus scho-lasticus, is presented in nuclear form, leaving to the reader’s discernment, learning, logic, and intellectual energy its unfolding and full development. An isolate voice, crying from the desert. Vox clamantis in deserto is a role that few care to play, but I find pleasure in it. The voice crying from the desert, with its righteous assumption of enlightenment, tends to grate on the nerves of the multitude. But it is mine. I’ve had to learn to live within a constant blizzard of abuse from book reviewers, literary critics, newspaper columnists, letter writers, and fellow authors. But there are some rewards as well: The immense satisfaction, for example, of speaking out in plain blunt language on matters that the majority of American authors are too tired, timid, or temporizing even to allow themselves to think about. To challenge the taboo—that has always been a special delight of mine—and though all respectable and official and institutional voices condemn me, a million others think otherwise and continue to buy my books, paying my bills and financing my primrose path over the hill and down the far side to an early grave. Yes, it’s true by God, whatever I’ve accomplished as a writer, I’ve done on my own, without any encouragement from my ” fellow” authors and against first the indifference and then the resolute opposition of the guardians of our contemporary Kultur.

Kultur, I say, not civilization; when or where has a true civilization, worthy of the respect of honest men and honorable women, ever existed ? Name me one organized human society, ethnic group, race, or nation, modern or historic, that does not deserve—on due consideration—our most generous contempt. A few exceptions come to mind: perhaps the Finns, the bushmen of the Kalahari, the Hopi of Arizona—those who have committed least evil in the world; but they are few indeed and they come from the remotest fringes of the anthropocentered hive—in so far as they still exist at all.

This sort of talk is called cranky, cantankerous, misanthropic. I have been called a curmudgeon, which my obsolescent dictionary defines as a “surly, ill-mannered, bad-tempered fellow.” The etymology of the word is obscure; in fact, unknown. But through frequent recent usage, the term is acquiring a broader meaning, which our dictionaries have not yet caught up to. Nowadays, curmudgeon is likely to refer to anyone who hates hypocrisy, cant, sham, dogmatic ideologies, the pretenses and evasions of euphemism, and has the nerve to point out unpleasant facts and takes the trouble to impale these sins on the skewer of humor and roast them over the fires of empiric fact, common sense, and native intelligence. In this nation of bleating sheep and braying jackasses, it then becomes an honor to be labeled curmudgeon. I accept the sneer with pleasure, as I would an honorary degree in roach control from the University of … well, Ockham. (The razor, William, the razor! No multiplication of superfluous entities!)

The Deserto in the title, therefore, denotes not the regions of dry climate and low rainfall on our pillaged planet but, rather, the arid wastes of our contemporary techno-industrial greed-and-power culture; not the clean outback lands of sand, rock, cactus, buzzard, and scorpion, but, rather, the barren neon wilderness and asphalt jungle of the modern urbanized nightmare in which New Age man, eyes hooded, ears plugged, nerves drugged, cannot even get a decent night’s sleep. While the grumbling, eccentric Vox, though isolated, may speak—I suspect—for the desperations and aspirations of many. Of very many, deprived by circumstance of the opportunity to speak for themselves. Where the means of communication fall within the control of a tightly centralized monopoly, free speech becomes a meaningless gesture, a useless privilege. When and if the opportunity does come, one must make the most of it or betray both thy neighbors and thyself.

The Deserto in the title, therefore, denotes not the regions of dry climate and low rainfall on our pillaged planet but, rather, the arid wastes of our contemporary techno-industrial greed-and-power culture; not the clean outback lands of sand, rock, cactus, buzzard, and scorpion, but, rather, the barren neon wilderness and asphalt jungle of the modern urbanized nightmare in which New Age man, eyes hooded, ears plugged, nerves drugged, cannot even get a decent night’s sleep. While the grumbling, eccentric Vox, though isolated, may speak—I suspect—for the desperations and aspirations of many. Of very many, deprived by circumstance of the opportunity to speak for themselves. Where the means of communication fall within the control of a tightly centralized monopoly, free speech becomes a meaningless gesture, a useless privilege. When and if the opportunity does come, one must make the most of it or betray both thy neighbors and thyself.

So: This, reader, is an honest book. (Never mind the occasional self-contradictions.) It warns you at the outset that my sole purpose has been a private and egocentric one. I have no thought of serving others; such ambition is beyond both my intention and my powers. I am myself the substance of my book. There is no reason why you should waste your leisure on so frivolous and unrewarding a subject. Farewell then, from Abbey, on the parapet of the tower at Port Llatikcuf, Arizona, in this windblown, dust-obscured midday twilight on this third day of March in the year 1989 anno Domini.

E.A. March 3, 1989 Fort Llatikcuf, Arizona

![]()

CHAPTER 9 – On Nature

Us nature mystics got to stick together

+

Wilderness begins in the human mind.

+

I come more and more to the conclusion that wilderness, in America or anywhere else, is the only thing left that is worth saving.

+

Narrow-minded provincialism: Sad to say but true—I am more interested in the mountain lions of Utah, the wild pigs of Arizona, than I am in the fate of all the Arabs of Araby, all the Wogs of Hindustan, all the Ethiopes of Abyssina..

+

If wilderness is outlawed, only outlaws can save wilderness.

+

The developers and entrepreneurs must somehow be taught a new vocabulary of values.

+

It is not enough to understand our natural world; the point is to defend and preserve it.

+

A new conservative must necessarily be a conservationist.

+

The industrial corporation is the natural enemy of nature.

+

Concrete is heavy; iron is hard—but the grass will prevail.

+

The world exists for its own sake, not ours. Swallow that pill!

+

God bless America. Let’s save some of it.

![]()

For those most passionate about nature, Abbey is a God. The man gave everything to the desert he worshiped. He earns my respect, but alas, not my love.

He decries too many things that are holy to me. The indigenious people he so admires often suffered unbelievable pain for things that civilization has greatly alleviated. I love the creativity and sensitivity that goes into making a china cup, the beauty of a mosque or a temple, the printed words that others left behind.

Without civilization we would have no Shakespeare, no

Hemingway, not even an accessible Edward Abbey.

I salute him, but I do not kneel at his shrine. Barbara Fitz Vroman

alas for he is gone these 19 some years. it seems as thou it was only a fortnight ago when i crossed his path at the bookstore on the mall in the “Hole”. i still have both the signed copies from him, he had a sparkle in his eyes as he spoke of the wilds of the gros vonte that hot july day.

if you want a true outlook on the west, read his speech on cowboys and cattle from the university of montana…

blessed are the cracked for it is they that let in the light…