Poetry Dispatch No.230 | April 24, 2008

Earth Day Week, April 2008:

MARY OLIVER: Good or Bad?

One way or another, if you put your life on the line in search of meaning and/or art: the critic is bound to eventually enter the scene and have his way with you. The longer you’re out there, the more work you have to show for it, the greater the chance ‘the critic’ (outside your own friends and family) will come along and either praise you to high heaven or damn you to hell.

“I think, therefore I am.” Yes, of course.

“I write (paint, act, make music, etc.) therefore I am subject to interpretation, damnation, edification, criticism, humiliation, etc.” you better believe it.

On the upside, if you’ve been hit hard enough, often enough, you learn how the game is played and either close your eyes and walk away from it forever, or foolishly waste time hitting back, trying to gain the upper-hand, the last word.

In a very few instances, you may actually learn something. But that takes a particularly perceptive critic.

What has all this to do with Earth Week? Nature Poetry? Mary Oliver?

You will have to figure that out for yourself.

Here’s an intriguing essay by Jough Dempsey of www.plagiarist.com which may help.

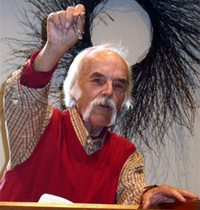

It sent me rushing to my bookshelves to discover with delight once again, that rare sight of thirteen blackbirds living forever so perfectly in a poem by Wallace Stevens. Norbert Blei

![]()

You Do Not Have To Be Good (But It Helps) — A Look At Mary Oliver

by Jough Dempsey www.plagiarist.com

Admittedly, I’m predisposed to disliking “nature poems.” Maybe it’s because many are facile, easy to write, and make the kinds of observations only an idiot needs spelled out in poetry. It’s not that a good nature poem can’t be written – it’s just that so many poets have written poor ones.

So I’m in a bit of a quandary when it comes to writing about a poet who’s made a career out of writing bad nature poems. Mary Oliver is technically proficient, and from reading her prose works about poetry (her A Poetry Handbook is probably one of the best introductory volumes about poetry ever written) I believe that she knows a lot about poetry. So why are her poems so god-awful?

That Mary Oliver is a grossly overrated poet isn’t really the issue. She’s very easy to digest, and, since her poems take no risks, there’s little to offend in them. The following is emblematic of what’s wrong with Mary Oliver’s poetry:

![]()

Wild Geese

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

![]()

Gee.

This isn’t the usual creative-writing-program-produced pap—no, this is highly-crafted, meticulously-designed, carefully-thought-out archetypal creative-writing pap. It takes a well-educated poet to write a poem this bad.

I was actually a bit hopeful by the first line. But then as I continued my enthusiasm waned, much like the steam driving this poem. It’s like a balloon with a slow leak, hissing along until the last lines push the air completely out, leaving a wrinkly piece of plastic on the floor, to later get caught in the gears of the vaccuum cleaner and cost $143 (U.S.) to repair, resulting not only in dirty carpets for the duration of the cleaner’s time in the shop, but also a small bald spot on the top of your head from where you scratched it trying to figure out how a balloon wound up in your living room…

Okay, maybe I got carried away with my own metaphor there. “Meanwhile the world goes on.” Really? It does? I mean, come on! The world does not call to me like wild geese. I’m not really sure what to “latch onto” in this poem, because the images (such as they are) are so vague and “first-level” – here’s a tip: just because you use the words “mountains” and “rivers” in your poem does not mean that they’re going to be in there. Those are just words. You have to do something with them if you want to make poetry.

Mediocrity Abounds!

The problem with “Wild Geese” is not that it’s vague, which it is, but that it’s completely spineless – what’s the message, ultimately, of this poem? “You have a place in this world and like the geese, are free because of your imagination!”

Assuming for a second that this is true, who needs to be told this? A useful tool for revision is to take a statement from a poem, and then state its opposite – if the opposite is ridiculous (i.e., doesn’t need to be said), you don’t need to make the original statement. This poem is like an advertising slogan, telling you that the company’s product is great. Of course it is. What else would they say?

The danger creeping into contemporary poetry (it’s been happening for years, but is growing) is the flattening of the image, the death of risk. Using nouns in a poem inserts an object into the poem, but for that object to become an image it must be acted on by the poet. Something needs to happen to the object. Here’s another little gem:

![]()

I was standing

at the edge of the field–

I was hurrying

through my own soul,

opening its dark doors–

I was leaning out;

I was listening.

— from “Mockingbirds”

![]()

Like a sugar pill, this poem seems to be doing something, but isn’t, really. I’ll let her vagueness go for a minute and stop to shudder on the phrase “hurrying / through my own soul, / opening its dark doors–”

This is the kind of adolescent angst that would be barely forgivable if a teenage girl wrote it. Coming from Oliver, who should know better, this is shameful. Angst-ridden posturing doesn’t ever make a poet sound “cool” or “deep,” especially since referring to your “soul” as “dark” is hardly original, and usually the work of the shallow and simple-minded.

And again, what’s her point? As I click through her work in the archive I have a hard time figuring out why each poem was written. What is she trying to say? She seems to have a preternatural aversion to making a point.

Oliver’s poems lack the immediacy of haiku, the punch of Robert Frost, the gorgeous language of Wallace Stevens – here’s a snippet from Steven’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking At A Blackbird”:

XIII

It was evening all afternoon.

It was snowing

And it was going to snow.

The blackbird sat

In the cedar-limbs.

This is a nature poem with punch–with purpose. I understand, after reading it, why it had to be written. This is what Stevens called the “occasion” of the poem – it’s the reason that should be readily apparent as to why the poet wrote the poem, why the poem needed to be written. Oliver’s poems are lazy, and unnecessary, because it may have been preferable for her to go shopping than write the poem. If a poem’s raison d’être is that the poet had nothing better to do on a Saturday afternoon, one (such as I) really has little reason to read a poem that had such little reason to be written.

You’re just jealous.

I’m dumb-founded that anyone would not find these poems anaemic. Mary Oliver has won numerous awards for her poetry. Why is she so popular? I think it’s because her poems are weak – you can “take in” a Mary Oliver poem in one reading – and probably after simply hearing it once. As readers grow lazier, more poetry like this will continue to be written, and the worst of it, that which seeks to affirm life while slothfully numbing the experience of the poem so that no one gets offended, will win awards because to awards-giving bodies, it feels good to acknowledge poetry that’s both lackluster and easily digestible. Awarding Mary Oliver is lending legitimacy to the “poem as sound bite” that’s very easy to promote to young readers, because it’s “positive,” “uplifting,” and doesn’t take a lot of unpleasant thought to read.

Reading Oliver is an exercise in futility, and so is this article, really, because if you’re already not a fan of Oliver, I’m not going to set you against her, and if you are a fan, I’m not likely to change your mind. It’s okay. I’ll just hope that someday you’ll learn more about how a poem works, read some good poems, and will come to appreciate poems that don’t “give up their secrets” on the first read. You do not have to read good poetry, but given the choice, why read Mary Oliver?

Jough Dempsey is a poet & critic and the webmaster of Plagiarist.com, an online poetry resource for both the Sharks and the Jets. In his spare time he enjoys ion beam lithography.

*I like to read the Poetry Dispatch. It’s almost like hanging out in a bar or coffee house, back in the day, yakking about poetry, literature, the state of the world, etc. Fun and interesting stuff. -Lyn Miner*

It takes an especially accomplished, self-appointed wordsmith to write bullshit masquerading as crap. So, you win Mr. Accomplishment … we’re all willing to let you go on believing you’re oh so much more intelligent than the rest of us boofers, out here in la-la land, trying to enjoy the written word.

You miss the whole point of poetry, or at least the point of this poem. So you don’t “get” what she’s saying. So you’ve never felt the way she felt when she wrote this. Then say that. You can’t understand how powerful this poem is if you’ve never felt this in the marrow of your bones. I find it hard to believe that you so harshly criticize something you don’t emotionally grasp–and isn’t that what poetry does to/for us?

YOU miss the whole point of the dispatch. Who is ‘you’?

It may be that the “soft animal” of Mr. Dempsey’s body has long ago been toughened up, callused, and hardened, to the point where it can’t be reached. That happens, unfortunately. This poem speaks to that part, and if that part no longer exists, than the words indeed are useless. like a key without a lock.